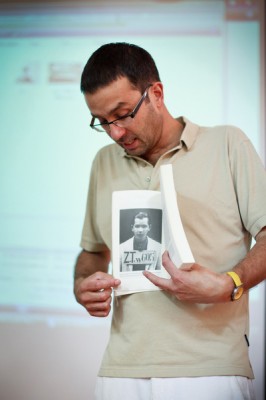

On the afternoon of June 23, 2010, the Department of History, University of Social Sciences and Humanities, held a book launch for the new book Immigrés de force: Les travailleurs indochinois en France (1939 – 1952) [Forced Migration: Indochinese Laborers in France (1939-1952)] by French scholar and journalist Pierre Daum.The book launch attracted considerable interest from faculty and students of the university, researchers, officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Vietnam Television. On behalf of the university's Board of Directors, Associate Professor Dr. Nguyen Van Kim attended and delivered the opening and closing remarks at the seminar. Author Pierre Daum's presentation provided a general overview of the history of approximately 20,000 Indochinese laborers (almost all Vietnamese) in France during the period 1939-1952. World War II led to a severe labor shortage in France's weapons factories, and the use of colonial labor was employed extensively. Unlike the people of colonial Africa, the Vietnamese did not participate much on the front lines but were mostly sent to military factories – where they had to work hard and were treated terribly, almost like slaves. “After a long, arduous journey at sea,” Pierre Daum recounted bitterly, “the Indochinese laborers landed in the port city of Marseille and were immediately thrown into prison before being organized into teams to work in military factories.” The harsh working environment, coupled with a lack of knowledge and experience, resulted in nearly 1,000 workplace accidents and fatalities.

The French defeat in the war (June 1940) further exacerbated the plight of nearly 20,000 Indochinese workers. French gunpowder factories closed, and Indochinese laborers were forced to return home. However, due to the ferocity of the war and the disruption of the sea route to Indochina, the repatriation of approximately 15,000 Indochinese was impossible. They were transferred to southern French regions such as Marseille, Toulouse, and Bordeaux. There, they were separated into groups of 2,000 to 4,000 people, living in seven camps under the supervision of French officers. Pierre Daum described: “Every day they had to work hard, in the evening they were allowed to walk around the camp, but they had to gather before 8 p.m., otherwise they would be beaten… They lived like in a prison, were treated terribly, and went hungry because the commanding officers cut their rations…” During their exile in southern France, these Vietnamese laborers left a historical mark on the agricultural cultivation of the Camargue triangle in southern Marseille. Due to the relatively similar natural conditions to Indochina, the local authorities considered using the aforementioned Vietnamese laborers for rice cultivation. This experiment yielded unexpected results, and since then, Camargue has become a major rice granary of France. After the end of World War II, the De Gaulle government planned to repatriate these laborers. However, the plan was not implemented before the French returned to reoccupy Indochina. The ships from France to Indochina were solely for transporting soldiers, not Vietnamese laborers. Vietnamese migrants were stranded in France, where they continuously organized activities demonstrating support for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam government led by President Ho Chi Minh. These politically motivated activities by the Vietnamese diaspora in France provoked a reaction from the people of Marseille, who demanded their deportation. France spent another four years repatriating these migrants. The repatriation process was only largely completed in 1952. Of the 20,000 Indochinese (the vast majority Vietnamese) forcibly migrated to France since 1939, approximately 18,000 returned home; 1,000 died, and 1,000 remained in France after 1952.

Few would have known about that turbulent chapter in the century-long history of Vietnam-France relations if scholar Pierre Daum hadn't painstakingly searched through archives, sifting through faded documents preserved for over half a century. For three years, following information from these files and traveling extensively throughout Paris, Marseille, Hanoi, and other regions, scholar Daum rediscovered 25 living witnesses – individuals who participated in the migration of 20,000 Indochinese people – to gather more information about their lives and harsh working conditions during the period 1939-1954. The book caused a great stir in political, social, and academic forums in many countries. At the end of 2009 (six months after the book was published by Actes Sud), the Mayor of Camargue organized a ceremony to honor the Vietnamese who pioneered rice farming, a practice still thriving in southern France. After seven decades, history has finally been brought to light.