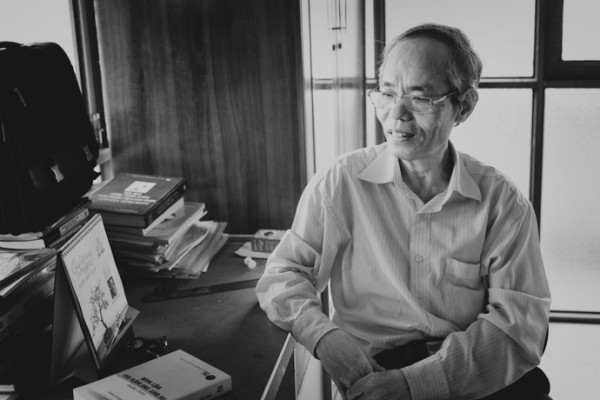

Simple, warm, yet full of scientific spirit – that was the impression of those who attended the seminar on the poetry collection "Luc Thap" by Associate Professor Dr. Nguyen Ba Thanh, organized by the Faculty of Literature in mid-June. On the sidelines of the seminar, Associate Professor Dr. Pham Thanh Hung (Director of the Center for Research and Application of Culture and Arts, University of Social Sciences and Humanities) shared many interesting insights.

The poetry collection "Sixty Years" by Associate Professor Dr. Nguyen Ba Thanh seems to have surprised many readers, friends, and colleagues in the Faculty of Literature. The collection offers a summary of 60 years of a lifetime and also demonstrates the sincerity and willingness to open up without hesitation or anxiety of a literature teacher at such a mature age.

For many, "Sixty" came as a surprise. Personally, as a friend, I anticipated that the sixty-year-old poet would release it. This collection of poems was initially motivated by the desire to express personal anxieties, to seek empathy and understanding from friends and colleagues. It is precisely because of this pure creative motivation that the collection doesn't bear the mark of a professional writer, even though the author himself is an expert in lyric poetry, a pioneer of the "Poetic Thinking" theory in literary research and criticism. Perhaps when writing poetry, the author sets aside his theoretical aspects, concealing his scientific side, allowing the poetry to resonate spontaneously. When sad, his poetry is melancholic; when happy, it is vibrant. His poetry is as natural as a clump of bamboo, swaying gently in the wind! Many close friends, understanding the life and career of Professor Bá Thành, encouraged him to publish it. In particular, his second wife, who loved his poetry (though it's still unclear what she loved first, the poetry or the man), "insisted" that he publish it.

The cover of the poetry collection features a hard tree trunk bursting with a cluster of flowers, which at first glance look like sim flowers, but according to the author, they are lim flowers. This species of flower blooms only once every 60 years. The author says so, but I don't quite believe him (because I'm very ignorant about wood and botany in general). However, when flowers enter poetry, everything else becomes symbolic. The collection of poems is like the "maturity" that has reached its peak, the poignant blossoming of the old lim tree after 60 years of accumulating life's blessings.

Although it was presented as a scientific seminar, it seemed more like a heartfelt sharing of feelings between friends and colleagues with the author. There appeared to be a great deal of generational empathy regarding the author's reflections in "Sixty"?

Many people share the sentiment that "we come to the person more than to the poetry." People come to the seminar primarily because they respect the person and character of Professor Bá Thành. And in the seminar, discussing poetry is also a way to discuss the professor's life, his way of living, and his way of thinking.

For example, Associate Professor Huu Dat, a poet of a "different style" but sharing the same circumstances of having two wives, expressed great admiration for author Ba Thanh when he spoke. He admired him because he had never seen anyone write poems praising both "two volumes" in one poetry collection. This was something he could only dream of achieving. Professor Bui Viet Thang, a renowned literary critic, spoke as a fellow student (Faculty of Literature, Class of 14). He recalled that Professor Ba Thanh and Professor Pham Gia Lam had to abandon their studies in 1972 and go to Baku, Soviet Union, to learn how to fire missiles: “That was strange, because how could humanities students possibly hit anything? They brought the missiles back but never fired them; it turned out that all the American planes had gone home, leaving nothing to shoot. The missiles arrived too late, and there was no chance to prove their talent. But today, with this seminar, Associate Professor Ba Thanh has fired a real missile. A missile in poetry.”… Of course, such lighthearted anecdotes are not just for the seminar's flavor, nor are they mere side stories. These stories are valuable information for readers to decipher the symbols in Ba Thanh's poetry. Without knowing about your trip to Ba Cu, how could I understand the poem you wrote: I hold an AK in my hand / With the price of ten tons of rice… I dream that the next time I visit / I will sell the AK to buy a rice mill / Sell the radar system to build a school / Sell the Sam-3 grenades to build a hospital with a thousand beds.

The theme of the seminar was "The Sixty-Year Poetry Collection and Personal and Social Inspiration in Contemporary Vietnamese Poetry." So, at the seminar, how did the experts assess the position and role of personal and social poetry in today's life?

With the publication of this poetry collection, our Literature Department is discussing personal and social poetry. This can be considered a new style of poetry, emerging after the era of revolutionary poetry. War and revolution in our country transformed poetry into a weapon, a common voice of the community's will. The epic tone in peacetime poetry subsided. From the heights of the battlements, people returned to face the worries of everyday life. Poetry followed suit.

Actually, this style of poetry isn't unusual. It has existed since ancient times, even in medieval poetry. Even within the mainstream literary tradition, personal and social themes were never suppressed. Nguyen Trai's vernacular poetry, Nguyen Du's classical Chinese poetry, and Ho Xuan Huong's poetry are all examples of personal and social themes. It's just that, due to war and revolution, we've become accustomed to "public life" poetry, so when poetry returns to personal life, we find it strange.

Indeed, personal and social poetry is becoming a mainstream trend in Vietnamese poetry today. This trend can flow parallel to other trends even within a single author. This inspiration can intertwine with other inspirations within a single poem or a collection of poems. Nguyen Duy's poetry is a prime example. The important thing is whether his personal life becomes a shared story, whether his individual self becomes the collective, or whether his writing remains merely fragmented tales of his home, his quiet village alley, and his hometown.

Some argue that this is not a "sophisticated" style of poetry, and if not handled carefully, the words and ideas in the poem could become "colloquial"?

Authentic poetry rejects categorization: high or low. For a long time, the art-loving public has turned its back on normative aesthetic notions. Poetry and art in general that try to appear "high-class" or morally superior is self-destructive.

Personal poetry – reflecting current events – is formally close to folk poetry, with an everyday, colloquial style, rather than being overly refined or rhetorical. It favors a natural style, close to the language of daily life. Writing about his father, the author Lục Thập summarizes it this way:Half a lifetime teaching classical Chinese / When the revolution came, they focused on worldly affairs / Party members dared not rest / Secretaries, Team Leaders… stood exposed to the sun in the fields.

The whispered opinion that Ba Thanh's poetry is simplistic and colloquial was probably inspired by the general advice of the poet Vuong Trong. The famous poet Vuong Trong – a close friend of Ba Thanh (who played chess all year round without ever winning against him) – said:Reading "Sixty," I pondered two concepts: vernacular and simplicity. Should poetry be vernacular or simple? Poetry that achieves simplicity must be the work of masters, because if it's too elaborate, it ceases to be poetry. Poetry must reach a state of essence, a simplicity that is profound and insightful, a simplicity that is the result of a distillation process. The boundary between simplicity and vernacular is very thin. Writing too vernacularly ceases to be poetry."

Mr. Vuong Trong spoke very profoundly, expressing the perspective of someone in the profession. He offered some subtle advice to the author of "Luc Thap," but I think the colloquialism in "Luc Thap" is intentionally colloquial. It lies within the author's conception of poetics.

How do you assess the upcoming trends in personal and social commentary poetry? To ensure that personal and social commentary poetry transcends the author's need for mere expression of emotions and becomes a valuable and meaningful work, what elements, in your opinion, need to be ensured?

In fact, the theme of personal and social commentary is merely a way of identifying the shift in the dominant tone of Vietnamese poetry since the war, especially since the Doi Moi (Renovation) period. Poetry, regardless of the era, if it's good poetry, begins with personal experiences, moving from the individual to the universal, touching the hearts of all. Therefore, predicting the nature of social commentary poetry is difficult and perhaps superfluous, as it's a fundamental rule of poetic creation. Social commentary and personal life are considered natural attributes of poetry.

Of course, for personal and social poetry to truly live on, the poet himself must fully experience the joys and sorrows of the people and the nation today. Only by understanding the pain of his fellow human beings and the nation can his personal pain become a shared pain. He writes about the personal but transforms it into a collective statement of the community. This is something Chế Lan Viên advised his friends and himself very well. And Associate Professor Dr. Nguyễn Bá Thành has even written a whole treatise on Chế Lan Viên's poetry.

It's clear that Associate Professor Dr. Nguyen Ba Thanh's collection of poems, "Luc Thap," is well-loved by many. Personally, what do you consider to be the most valuable aspect of this collection?

Teacher Thanh's poetry begins to reach a level of simplicity. Most valuable is that this is a poetic work that proves "the poet's style is reflected in his poetry." His poetry reflects his life as he lived it. Teacher Thanh's optimism, his wit, and his real-life pain are all reflected in his poems. Many poems are quite serious, but most are simply lighthearted. The most valuable aspect of this collection, "Sixty," is its sincerity. The beauty in his poetry lies in its straightforwardness. This beauty emanates from truth and innocence. It's no wonder that some people, upon first opening the poetry collection, are startled, thinking it's a family photo album, because interspersed among the poems are portraits of his parents, his two nephews, and his son's wedding. Only after reading the poems do they realize these photos serve an illustrative function. For him, anything with informational value—poetry, photos, couplets—is poetic and can coexist within the text.

The Faculty of Literature is quite famous for its many amateur poets with unique and distinct personalities. But it seems none of them intend to become "professionals"?

Let me clarify something. The opinion about amateur poetry came from the advice of Associate Professor Tran Ngoc Vuong. Professor Vuong wanted Mr. Thanh to reach the level of professional poet. But in my opinion, that advice is… foolish. At sixty, trying to “compete” with professionals is foolish, even inappropriate. Moreover, this is not the place to professionalize. Teaching poetry should only be about “playing” with poetry. The amateurism at “Sixty” is a deliberate kind of amateurism. For Mr. Ba Thanh, poetry is just a game.

Twenty years ago, when the total number of members of the Vietnam Writers Association was around 600, 25% were former students of Hanoi University. The Faculty of Literature was a breeding ground for poets. Graduates who stayed on to teach and conduct research often had to set aside their artistic talents, prioritizing scientific thinking and the growing responsibility of being a teacher. Therefore, the pen names used in poetry, from Hoang Xuan Nhi, Phan Cu De, Ha Minh Duc, to Nguyen Huy Hoang, Tran Ngoc Vuong, Nguyen Hung Vi, Dao Duy Hiep, Huu Dat, Nguyen Ba Thanh… were all accepted based on a different criterion: not whether they were professional or amateur poets, but rather the poetry of masters.

Furthermore, as the seminar's theme clearly indicated, this was a scientific event. Many poets and scientists from the Institute of Literature, cultural institutions, and colleagues and friends left the seminar feeling resentful because they weren't given priority to speak. The seminar was so lively and engaging that it was impossible to tell when noon arrived. The chairman had to interrupt, promising to speak again on the author's 80th or 100th birthday. Associate Professor Nguyen Ba Thanh's poetry collection truly opened up many issues concerning modern Vietnamese poetry, fostering a healthy academic and cultural atmosphere.