Because even after Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi's passing, many decades have gone by, but his academic influence, scientific enthusiasm, and the calm and composed demeanor of this revolutionary intellectual and teacher continue to spread and resonate like the ringing of a bell, extending into the 21st century.

Searching for a title for my nostalgic essay about Professor Nhi, I hesitated for a moment before four words flashed through my mind: "great professor." It couldn't be otherwise. To me, Professor Nhi was undoubtedly one of the towering figures of the university community and of the new Vietnamese education system. During his lifetime, he often jokingly remarked:I'm the longest-serving head of department in the world."We heard him repeat that phrase many times, especially when he compared him to Professor Nguy Nhu Kontum – 'the world's longest-serving rector.' When he said that, accompanied by his hearty, gleeful laughter, we immediately recognized the complex mix of self-mockery and pride. Because during the war and revolution, the positions of Rector and Dean of a university faculty didn't change with term limits. Those positions were synonymous with responsibility and prestige. Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi was like a locomotive, pulling the Faculty of Literature, University of Hanoi, through an entire term – the term of the anti-American war."

In my vivid student memories, the towering figure of Professor still stands tall, reminiscent of the ancient trees in Hanoi during the 1960s and 70s. This imposing impression of him is further deepened by my wartime memories.

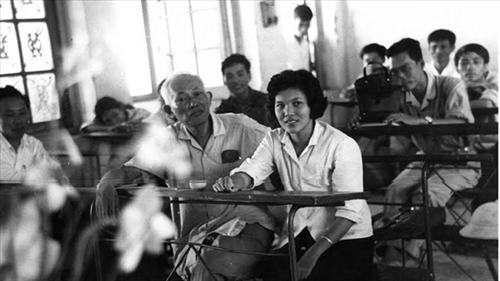

Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi and his students

In 1970, at the age of 16, I received my acceptance letter.Literature Summary– the abbreviated name of the Faculty of Literature – Hanoi University. My dream of a "university of Literature" that I nurtured for three years has finally come true. My university has the longest name for its Rector: "Ngụy Như Kontum," quite different from the names of other universities' Rectors, resonating like a poem. And my Faculty of Literature has the name of its head professor, "Hoàng Xuân Nhị," so gentle and warm!

When my father heard that I had been accepted into a department with a professor teaching me, he made me bring a pair of mats as a gift for the professor.If you want your child to be well-educated, cherish the teacher.I sympathized with my father, but he didn't sympathize with me. Looking at the bulky, smooth white bean mats sent from Nga Son, I felt utterly disheartened. How could I possibly get close to Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi, whom I only saw a couple of times throughout the semester, his coat fluttering by on his motorbike? In our T1/E104 class, the 15th cohort of the Literature and Linguistics majors, only a few of us skipped class to listen to Professor Nhi lecture to the older students. Every time he appeared on campus, our class would alert everyone to run to the windows and look down to admire him. My friend, a young man from Con Cuong, Nghe An province, even boasted that he had smelled the exhaust fumes from Professor Nhi's motorbike.The smoke smells nice, so the teacher must be using more expensive gasoline than car gasoline."He said that and then laughed; I didn't know if he was joking or serious."

1971 arrived for me amidst the joyful excitement of student life. It was the year the Faculty of Literature celebrated its 15th anniversary. My class created a wall newspaper, practiced performing arts, and regularly did physical exercises to celebrate. Initially, we planned a bamboo pole dance, but finding bamboo difficult to obtain, we abandoned that idea and switched to choral singing. We were both envious and impressed by the seniors – K14. They had a duet singing "Before the Shooting Festival," and a very pretty girl who dressed as a boy and performed the "Champa Flower" dance very skillfully. The Faculty organized a truly magnificent 15th anniversary celebration. The communal water tank of the Literature and History faculties was so large, yet the stage for the celebration was even higher than the tank itself. The performances were all excellent, but I was most excited about Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi's poetry reading. For so long, I had longed to hear his voice clearly. I heard there was a very good flutist who wanted to play along to accompany the professor's poetry reading, but after a couple of attempts, the professor dismissed the idea, saying his poems were very particular about music. Then it was the professor's turn. All the audience from both the Literature and History departments stood up and crowded around the stage. The speakers the department rented were a bit crackly, so the professor suggested reading directly to keep the poetry fresh. I managed to squeeze right up to his feet. This was the first time I'd stood so close to a professor. He was exactly as I'd imagined. A professor should be old, with gray hair, tall and imposing, dressed only for warmth, like Professor Nhi. His coat was definitely Western, not new, perhaps even a little wrinkled, but certainly elegant and very warm. In winter, with his coat, thin resident students like us could fit two under it as a blanket and sleep soundly until morning. The professor reached into his coat pocket. The pocket was very deep. He leisurely pulled out a cigarette, broke it in half, put half into the pipe, and before reading the poem, lit it, took a small puff, and smiled. The students clapped and cheered. It seems that poetry recitations have existed since that time.

The teacher began to read. His voice was that of Ha Tinh province, not resonant, slightly deep and husky, but it had a penetrating power, seeping into our hearts with each word like a drop of water falling in a cave.

But the soul of the youthful commune

Such a fortunate encounter only comes once in a thousand years.

Not far from the stage was a small road lined with old mahogany trees. Wanting to sit high up to watch the performance and listen to the poetry, many students mingled with the children and climbed the trees. The green platform couldn't withstand the heavy weight. Just as the professor's verses were most impactful, the audience in the trees simultaneously leaned forward, straining their ears to listen. The mahogany tree lost its balance, tilted, uprooted, and crashed down with a loud, half-shocked, half-delighted cry. On the stage, Professor Nhi continued reciting passionately, seemingly oblivious to what was happening. Some of my seniors commented: Professor Nhi's poetry is the poetry of a scientist, focused on content rather than form; though simple, it has the power to move even the roots of plants and people.

(1).jpg)

In September 1971, without having had a single class taught by Professor Nhi, twenty of us K15 students had to enlist in the army. Every male student in the class had to volunteer, but deep down, none of us wanted to go. Leaving after only one year of university was such a pity. We read the names of so many professors with their famous pen names: Dinh Gia Khanh, Bac Nang Thi, Ton Gia Ngan, Do Duc Hieu, Le Dinh Ky, Hoang Nhu Mai, Nguyen Van Khoa, Phan Cu De, Ha Minh Duc… with admiration and longing. We enlisted that year in the middle of the rainy season. The Red River was rising, threatening to break the dikes. Before the day of assembly and departure, I had the honor of moving books from the Literature Department library from the first floor to the fourth floor, in case the city was flooded. I carried stacks of books up to my chest, climbing the stairs step by step, my heart filled with uncertainty about the day I would return. After the war, I wondered if I would still be alive to read these books back in the department? Why did Professor Nhi, after studying in Western Europe, return to Vietnam to write textbooks on Russian literature and research President Ho Chi Minh's poetry? Such questions, of course, didn't bother my marching steps. However, throughout my years fighting on the Quang Tri front, I always encouraged myself that I was fighting for the peace of the University of Hanoi, where Professor Kontum and Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi worked, and that after the war, I would surely survive and return to the North, to that place.

The war wasn't over yet, and I was wounded. Luckily, I was able to return to school much earlier than many of my classmates. I had the opportunity to learn from Professor Nhi's impressive lectures. I also witnessed moments when he choked up because of Uncle Ho's poems. "First the devil, second the ghost, third the student." I don't know which class of students spread the anecdote that every year, Professor Nhi would cry at those exact moments, because his textbooks always included parenthetical reminders:This place is cryingAt first, I thought very seriously: if that were true, it wouldn't be funny, because it would be a sign of extraordinary talent, demonstrating pedagogical skill, an art of teaching. Because once, when I saw the teacher cry, I cried too.

Later I learned that those rumors, those anecdotes, were just a form of demystification by those mischievous literature students. The teacher's tears were real. They were sincere tears welling up from the innocent heart within the chest of an old man. Teacher Nhi lived with that youthful heart until the end of his life. Perhaps those were also the last tears of an era, sadly… that is passing by.

I think Professor Nhi belonged to the group of intellectuals born in the wrong era. These were Vietnamese scientists who had to live and work in a context where science wasn't a primary concern. It's said that when President Ho Chi Minh saw Tran Duc Thao returning from France to the resistance zone, eagerly accepting a task in the resistance, he jokingly remarked: "Thao has no place to call his own..." Tran Duc Thao went to work as a secretary. Tran Dai Nghia was assigned to manufacture weapons, which suited his expertise. Nguy Nhu Kontum, skilled in nuclear physics, temporarily took on an educational management role, saving resources. The resistance didn't yet need philosophy or nuclear weapons. Every intellectual had to sacrifice their strengths for the benefit of the resistance, working in areas where they were weaker. Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi was no different in his early years. Reading Professor Ha Minh Duc's writings, "Memories of a Teacher," I deeply understood this. Professor Duc believed that "if Professor Nhi had researched in the field of foreign literature, he would have been more successful." Many other professors also believe that Professor Nhi's research and teaching of Russian literature and President Ho Chi Minh's poetry stemmed primarily from a sense of responsibility as a pioneer, sacrificing his Western-educated expertise to venture into uncharted territory in need of exploration. Fortunately, thanks to his proficiency in French, German, and classical Chinese, he pioneered the fastest and most effective way, acting as a foundation-laying, pioneering figure, paving the way for his students and colleagues to follow.

Few people know that in 1936, Professor Nhi went to study in France on a scholarship from the Association for the Promotion of Studying Abroad, specializing in literature and philosophy. Just one year later, he graduated with a Bachelor of Philosophy degree (in 1937). During his time in France, he translated many classic Vietnamese literary works such as "Luu Binh Duong Le," "Chinh Phu Ngam," and "Truyen Kieu" into French, as well as works on Russian literary history and works by M. Gorky and Mayakovsky, which were published in magazines.Mercure de FranceIn 1946, he returned to Vietnam to participate in the resistance movement, taking charge of the cultural sector in the South. In 1947, he was assigned by the Southern Resistance Administrative Committee to be in charge of the newspaper.La Voix Du Maquis(Voice of the Resistance) was the first foreign-language newspaper in the revolutionary war zone. Along with the newspaperLa Voix Du MaquisThe resistance government's propaganda work led European and African soldiers in the French army to desert and join the resistance in the resistance zones. Because of his proficiency in English, French, German, and Russian, he was assigned by the committee to be the political commissar of the international contingent of soldiers who had deserted from the French army. In 1947, the resistance government appointed him director of the Institute of Resistance Culture. When the cultural sector was unified with the education sector, he was appointed director of the Southern Education Department. In 1949, Hoang Xuan Nhi participated in opening a special teacher training class named after Phan Chu Trinh to provide cultural training for the resistance forces.

After the Geneva Accords, he relocated to North Vietnam, was appointed professor, and taught at the Hanoi University of Education and the Hanoi University of General Studies from 1956 to 1982. He served as head of the Faculty of Literature at the University of General Studies and was also a founding member of the Vietnam Writers Association and the Vietnam Association of Arts and Literature.

In 1978, after graduating, I was fortunate enough to be assigned to the Department of Literary Theory and Modern Vietnamese Literature alongside Professor. Although we worked together for nearly a decade, Professor still didn't remember my name. I wasn't too upset about that, because I had a comforting example. Nguyen Ba Thanh, who was so talented at the time—not only was he excellent, but he also worked for the union and delivered Professor's salary to his home every month—only had half of his name remembered by Professor. Professor would often nod, indicating he knew Thanh's name well:I remember your name now, comrade, Nguyen Ban, I miss you so much."If I, Pham Thanh Hung, were to join the labor union and contribute my salary, I'm sure the teacher would remember me in this way:Pham Han… I love him so much.That's all.

In the post-war 1980s, I'd never felt life was so depressing. The salary of a young university professor wasn't enough to live on for more than a few days. I mainly relied on my mother's salary back home. My parents loved the prestige of having a son who taught at a university, so I exploited them financially. Every few months, I would write letters threatening to quit my job and transfer to another institution. My parents, afraid, would send me money and encourage me. After being tricked for several years, one day, after hearing my threats, my parents unanimously declared: "Just quit your job then! Who's going to support you until you're old?"

Having lost all support, I threw myself into studying Russian to forget my hunger. That was also the period when Professor Nhi reminded and encouraged me. I don't remember his name, but he knew I was in charge of the literary theory curriculum. Once, he asked: "Comrade, what's new in Russian and Western literary theory this past year?" I was speechless, unable to answer. After hearing my story, he told me: "You have to try harder; in the old days, you could read magazines fluently in Russian after just a few months." Following his example, I put aside all my worries and diligently consulted dictionaries and practiced translation.

Once, when I visited my teacher's house, I complained about the hardships of life. He looked at me for a long time and then said something that I will always remember:I'm a professor, and I still have to wake up early to fetch water and queue up to buy cheap vegetables."The teacher said, then leisurely took a puff of his pipe, gazing at the wall in front of him for a long time. Of course, there was nothing remarkable about the wall. He looked melancholic, lost in thought, imagining things. After a while, he uttered a few words, as if speaking to himself:"The important thing is that the country is unified!"

I walked out of the teacher's room, out of Block D of the Kim Lien apartment complex, carrying his words with me like a canteen of refreshing water during wartime. In turn, I looked up at the blue sky:The country is unified now!"That's a truth, an everyday truth, a genuine happiness, a happiness every day, why didn't I remember? Several times lying beside the bodies of my comrades, I longed for and dreamed of peace, yet still considered it a pipe dream. For years now, peace has truly come, the country is unified, why did I forget? Teacher Nhi reminded me of the greatest, most fundamental value of national life. He instilled in me a belief. Difficulties will pass, unification is here, and we will have everything. I know he believes that. If he believes, then I believe too."

The country in the post-war years was truly impoverished. After the initial joy and excitement of ending years of suffering and death, breathing in the breath of peace, and the misconception about the nation's future, we began to feel bewildered and disappointed by the country's economic prospects. At that time, the whole country was starving. We young teachers didn't dare play sports because even a few minutes of exercise would leave us hungry. The communal kitchen wouldn't ring the bell for meals until 11:30. Usually, by 10 o'clock, my stomach would be rumbling, making me restless and unable to read. One young teacher, so hungry, decided to fall in love with a cafeteria worker so she would give him an extra piece of burnt rice at each meal. Fortunately, that opportunistic romance eventually turned into a wedding. I had a short story that won the Army Literature and Arts Award. So hungry, I invited Ba Thanh to go with me to the editorial office to receive the award, plotting to sell the prize to buy pho. Why keep it as a memento? We weren't fame-seekers, but ultimately, we were starving. I'd sell anything, whether it was a Kim Tinh fountain pen, a Rang Dong thermos, or any kind of cup or saucer. I'd sell them at black market prices… Around noon, we were starving when Thanh and I received our prize. We were overjoyed and went to a secluded spot to ask where we could sell it. When we opened it, we discovered the prize was a statue of President Ho Chi Minh from Pac Bo, along with a copy of the Party's history. We hugged the statue and carried it back, half smiling, half crying all the way on our march.

It was during those years of hardship that Professor Nhi emerged as an exemplary figure of overcoming adversity. He would stay up all night reading and writing. He even contributed papers opposing Beijing's expansionist ambitions. His Western-educated intellectual style and patriotic sentiments transformed him into an uncompromising opponent of hegemonic and expansionist ideologies. On one occasion, he even resorted to using vulgar language to curse the invading rulers, right in the middle of a scientific conference.

One year, Professor Ha Minh Duc took students from the Literature Faculty on a field trip to write about good deeds and exemplary individuals at Military Hospital 103. Perhaps thanks to Professor Duc's diplomatic skills, at the end of the internship, the Institute organized a very formal farewell and thank-you ceremony. "Forty-hearted"—those two words, whispered among ourselves at the time, meant... a drink. I was overjoyed. My stomach was churning with excitement. Just before the farewell party, Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi suddenly rode his motorbike into the courtyard. Before the motorbike's smoke had even cleared, Professor Do Xuan Hop—the Director of the Institute—rushed out to greet him. The two gentlemen embraced, saying something in French that we couldn't understand. I and the entire group of student interns followed them. Several French-speaking students followed along, eavesdropping and understanding bits and pieces, occasionally translating for us, which was quite enjoyable. However, listening too much became tiresome. The Institute's courtyard connected to the Military Medical University's campus, so it was very long and wide. We didn't know where the party was being held, so it was best that we stuck close to the two professors. Back in ancient Greece, Aristotle and other philosophers would lead their students into the forest for academic dialogues, probably something similar. The two professors, one studying President Ho Chi Minh's poetry, the other anatomical studies—two fields so far apart—were chatting animatedly and enthusiastically. When the professors walked, we followed; when they stopped, we, their disciples, also stopped, trying to maintain a distance that was both intimately familiar and respectfully appropriate. Following the professors, we couldn't possibly get lost. Believing this, we followed them for half an hour. Some impatient people considered leaving and separating, but when we saw the host professor leading Professor Nhi into a house, we excitedly followed. But after a while, we realized we were lost. We didn't know which way the two professors had turned. A moment later, Professor Nhi ran out and scolded us:I'm not talking about literature or poetry, why would I follow along? I'm asking Professor Hop for his opinion on the urinary tract.Professor Hop, the host, added:We're looking for a place to relieve ourselves. No eating. The party is being held in the dorm area. If you need to use the restroom, go in there and then come over."

We burst out laughing, jogged back, and easily covered nearly a kilometer.

I remember and recount this story not with the intention of humor. I only want to affirm one thing: a time of hardship has passed. But that was a time when we lived by faith. We loved our teacher, we believed in him. Everything he did was right, so following him, even if it was far, gave us peace of mind knowing we wouldn't get lost.

In 1990, I returned to Vietnam after five years as a postgraduate student in Prague. I came back almost empty-handed, without money, without a degree, but most importantly, without my associate doctorate. The "Velvet Revolution" of 1989-1990 had swept away many things in the "capital of a hundred golden towers," including the speck of dust that was my dissertation on Czech socialist realism. Czech education and academia abandoned communist ideology and Marxist methodology, so I had to rewrite my dissertation. My supervising professor was dismissed and fired. I didn't have the courage to seek help from exiled professors abroad. I abandoned my unfinished dissertation and returned home. I returned in melancholy and with a heavy heart, burdened by the painful experiences of a violent and swift revolution beyond imagination. I wanted to meet many friends and colleagues, to meet Professor Nhi, to tell him that the world was changing. Of course, that was just an intention. Nobody had time to listen to me or believe me.

After years of tireless research, teaching, and dedication, Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi's apartment remained unchanged, its old plaster still intact. Only his footsteps had changed: they became shorter and slower. No one in the Kim Lien apartment complex could forget the way he walked through the streets in his final years. Some compared those footsteps to those of the lonely old man Jean Valjean, who had lost Cosette – his last source of comfort. Professor Ha Minh Duc recounted that in his final year, Professor Nhi's strength waned rapidly. But when people visited him on his sickbed, he still made promises and offered encouragement:Comrades, please hold on to your faith. When I recover from my illness, I will write a report to the Central Committee on the issue of intellectuals, highlighting the successes and shortcomings in intellectual work.”

That's it. Until the very last moment, Professor Hoang Xuan Nhi lived by his faith. He believed in the Central Party Committee, he believed in himself. He believed in his ability to influence others, and that this influence would bring happiness to others. His dying words (try to hold onto your faith) reminded me of Professor Tran Van Giau's opinion upon hearing the news of Professor Tran Duc Thao's persecution after the Nhan Van-Giai Pham affair: "In any case, treating intellectuals like that is wrong, especially someone like Mr. Thao."

Professor Tran Van Giau was concerned with a single victim, a typical case. Our teacher, Mr. Nhi, was concerned with the majority – all of us. And going even further, he thought about relationships.The Party and its work with intellectuals.

In 1991, after Professor Nhi passed away, following his instructions and the family's wishes, the Department of Literature inherited his entire library. I and Mr. Nguyen Ba Thanh (again, Mr. Thanh) were assigned the task of taking over and arranging for a cyclo to transport the library to the Department.

Stepping into the room, I felt a chill run down my spine. I had felt a similar chill when I read To Huu's description of the stilt house after President Ho Chi Minh's death: "Three empty rooms, devoid of incense smoke." But now, in Professor Nhi's library, the room before me wasn't empty; on the contrary, it was cramped, and I still felt a shiver. Professor Nhi's office was crammed with books. Rows of German, French, and Russian books, atlases, and large, heavy dictionaries—like the cobblestones of an ancient European square. Someone once philosophized: a library is a kind of graveyard, for books are like the remains of human intellect…

Lacking the money to light incense and ask permission to remove the first book from the shelf, I clasped my hands for a moment in remembrance of my teacher: The books he wrote and read didn't bring him wealth, mansions, or cars. They only brought him fame and faith. And Teacher, if you had been less trusting, less blindly believing in that pure, classical communist faith, and had lived with skepticism earlier, surely your old age wouldn't have been so difficult.

Lieu Giai, May 14, 2014

Author:Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pham Thanh Hung

Newer news

Older news