1. Search for and select a solution.

Historical facts show that, based on the achievements in the dry season campaigns of 1965-1966 and 1966-1967, as well as the victory in the fight against the destructive war in the North, our Party Central Committee had early contemplated the possibility of opening a new battle with the motto: "Fighting and negotiating at the same time". However, the domestic and international political situation did not yet ensure the necessary conditions for the implementation of this possibility. By 1967, the 13th Central Committee Conference, held from January 23-26, proposed the policy of stepping up the diplomatic struggle against the US. Resolution No. 155-NQ/TWOn stepping up diplomatic struggle, proactively attacking the enemy, serving our people's cause of fighting against America and saving the countrycommented: "In the current international situation, with the nature of the war between us and the enemy, diplomatic struggle plays an important, positive and proactive role. We attack the enemy diplomatically now isat the right time”(1). From then on, along with politics and military, official diplomacy was considered an important front,has strategic significancecontribute to the victory of the resistance

That decision opened a new situation for the diplomatic struggle with the initial basic goal of demanding that the US unconditionally and permanently end the bombing and all other acts of war against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Implementing the above policy, on January 28, 1967, in an interview with Australian journalist W. Burchet, Foreign Minister Nguyen Duy Trinh declared: "Only after the US unconditionally and permanently ends the bombing and all other acts of war against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam will the Democratic Republic of Vietnamcan talkwith America”(2). This was the beginning of a series of attacks on the diplomatic front in the spirit of Central Resolution 13. Faced with our attitude, on February 8, 1967, US President Lyndon Baines Johnson sent a letter to President Ho Chi Minh informing him that the US would stop bombing North Vietnam on conditional terms. Following his instructions, we “responded publicly in the press to make Johnson even more confused, and if we reported that Johnson sent a letter to President Ho Chi Minh, the Saigon puppet army and government would be even more confused”(3).

Uncle Ho and the Politburo met to discuss the 1968 Tet Offensive.

At the end of 1967, due to facing increasing pressure from international public opinion, as well as many domestic socio-economic problems and the rising anti-war movement of the American people, at the National Constitutional Convention held in San Antonio, US President LB Johnson had to declare: “The United States is ready to cease all air and naval bombing of North Vietnam when this initiative leads to effective discussions. Of course, we assume that during the time those discussions take place, North Vietnam will not take advantage of the cessation or reduction of bombing” (4). LB Johnson’s conditional declaration of cessation of bombing was called by international public opinion “Antonio's FormulaOn October 29, 1967, to gain the initiative and demonstrate our goodwill to public opinion, in a speech on January 28, 1967, on behalf of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Minister Nguyen Duy Trinh again declared: “After the United States unconditionally ceases bombing and all other acts of war against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam will…”will talkwith the US on related issues”(5).

In parallel with diplomatic activities, on the southern battlefield, our armed forces continued to step up military attacks. Implementing the 14th Central Resolution on the Southern Revolution, along with the Khe Sanh front, on the night of January 30, 1968, the Tet Offensive and Uprising took place throughout the South, directly attacking major cities such as Saigon, Hue... The offensive dealt a heavy blow to the US's invasion plot and "prestige". In a strategic defeat, on March 31, 1968, LB Johnson declared to the American people that he was ready to "open peace talks immediately" and "ready to send representatives to any forum, at any time, to discuss measures to end this devastating war". According to him: "There is no need to delay negotiations that can lead to an end to these protracted and bloody wars" (6). LBJohnson's statement has three basic points: 1.Unilaterally cease bombing the North from the 20th parallel northward.; 2.Not running for a second term.; and 3.To negotiate with the Democratic Republic of VietnamAlong with acknowledging that he was “seeking to de-escalate the war,” on the first point, the US President pointed out: “The area where we are no longer bombing accounts for approximately 90% of the population and most of the territory of North Vietnam, except for the area north of the demilitarized zone” (7). To substantiate his words, LB Johnson also sent Averell Harriman, considered a skilled diplomat with extensive experience in negotiations between the US and Russia during World War II, to represent the US President and assigned A. Harriman the task of “seeking peace.” This can be considered a manifestation of strategic changes in US policy on the Vietnam issue. The US accepted de-escalation of the war, agreed to negotiate to explore and seek a political solution.

US President Johnson meets with advisers after the 1968 Tet Offensive

On May 13, 1968, after a period of debate and location selection, the bilateral conference between the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the United States officially held its first session at the International Conference Center on Kléber Street, Paris, France. Because we had not yet gained absolute superiority on the battlefield, the main motto of our delegation at that time was to force the US to unconditionally end the bombing of the North before discussing other issues. On October 21, 1968, our Government delegation officially issued a notice to the US side requesting the US to end the bombing and other acts of war against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and organize aFour-party conferenceto find a political solution to the Vietnam problem. The US accepted that proposal. The presence of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam negotiating delegation as a legitimate and official political entity not only enhanced the Front's standing and contributed to the world's understanding of our people's just struggle, but also strengthened the coordinated military, political, and diplomatic efforts between the North and South.It was a victory of strategic significance..

Although negative reactions from the Nguyen Van Thieu government were anticipated, the US's acceptance of the four-party conference with the presence of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam delegation caused serious disagreements between the US and the South Vietnamese government. LB Johnson bitterly admitted: "When we reached an agreement with Hanoi, the harmony with President Thieu broke down" (8).

Delegation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam attended the opening session of the Four-Party Conference on Vietnam in Paris on January 25, 1969

Faced with the rapid developments of the negotiations, the Nguyen Van Thieu administration wanted to extend the time to talk directly with Hanoi and relied on the support of some forces in the US Republican Party to reject LB Johnson's statement on ending the bombing and opening a four-party conference to resolve the Vietnam issue. The reason given by Saigon was that it needed time to seek the opinion of the National Assembly. Moreover, Thieu did not accept the National Liberation Front as a party to the negotiations and suggested that "procedural issues" must be resolved before the meeting. In his statement in Saigon, Thieu also made it clear that he was not ready to send a delegation to Paris to attend the conference as the US side had suggested.

Faced with that attitude of the Nguyen Van Thieu government, unable to miss the opportunity for peace, the US decided to "go it alone". LB Johnson ordered an end to air, naval and artillery bombings of North Vietnam. On the other hand, to reassure Thieu, Washington also explained that the participation of the National Liberation Front in negotiations did not mean legal recognition of this Front. Under pressure from the US, on December 8, 1968, the Nguyen Van Thieu government had to send a delegation to Paris to participate in the peace talks and directly witness part of the diplomatic struggle that was intelligent, skillful, and principled, maintaining our sovereignty and national independence. Saigon understood that: When the Americans accepted negotiations, stopped bombing and later accepted to withdraw troops from South Vietnam, the end of a pro-US puppet government was certainly not far away.

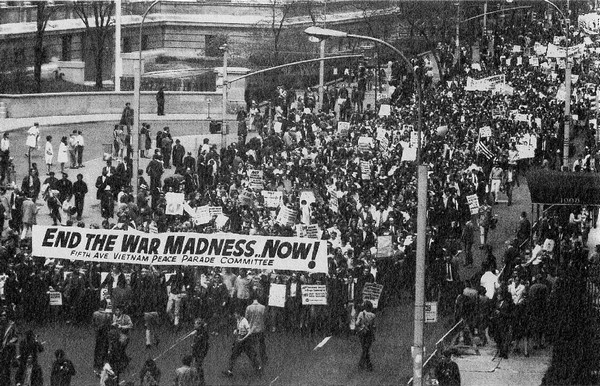

Anti-Vietnam War protest in New York in 1968

2. The Paris Conference: Commitment vs. Non-Commitment

On November 6, 1968, Richard Nixon, the Republican candidate, was elected President of the United States with 43.3% of the votes in the context of the United States being bogged down in Vietnam, and the political interests and economic position of the United States in the world being seriously weakened. Like his predecessor, R. Nixon soon realized the deadlock and disappointment in the war being pursued in Vietnam but still did not easily admit defeat. After the Tet Offensive, R. Nixon became even more convinced that the war could hardly be “won” by using force alone. After becoming president, the head of the White House issued the “Nixon Doctrine” on Guam Island on July 25, 1969. In the face of defeat on the battlefield and the need to withdraw troops sooner or later, the “Nixon Doctrine” was based on three principles:The power of America;Share the responsibility.andNegotiate from a position of strength.At the same time, on the international level, the US sought to “improve” relations with the Soviet Union and China in order to find the most beneficial political solution to the “Vietnam Problem”, cutting aid to Vietnam and on the other hand, taking advantage of these countries to influence the Vietnam-US negotiations in Paris.

Applying the principles of the "R. Nixon Doctrine" to the ongoing war in Vietnam, the White House implemented the "Vietnamization of the War" strategy to reduce America's commitment to its allies, requiring allies to gradually replace American troops fighting directly on the battlefield and withdraw troops from the country... The ultimate goal was to maintain the pro-American government in South Vietnam. In reality, this policy also aimed to appease the outrage of the American people, reduce the burden of the war, but continue to maintain influence in the South through arms aid and military advisors. Faced with the increasingly weakened and inevitable defeat of the puppet regime, the US implemented compromise measures, drawing in several countries to share and maintain interests and influence in Southeast Asia while continuing the long-term division of our country.

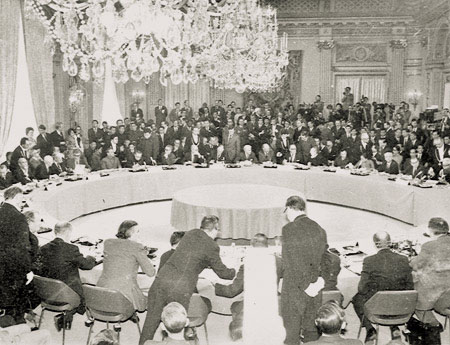

Overview of the Paris Conference on ending the war in Vietnam

However, with his belligerent nature, in 1970-1971, R. Nixon expanded the war to all three Indochinese countries to prevent the development of the revolutions in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia and to gain leverage at the negotiating table. After the 1968 Tet Offensive, American public opinion increasingly believed that invading Vietnam was a grave mistake. The anti-war movement had strongly infiltrated American intellectuals and university students. Many Americans believed that inflation, urban problems, and unrest in universities were all consequences of the Vietnam War. In the American economy, inflation peaked in 1969-1970. In the first year of R. Nixon's administration, the budget deficit was 3 billion USD and increased to 23 billion USD in 1971. That economic situation made the President of the Bank of America, Louis B. London, speak before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on April 15, 1971: "It seems to me that the time has come to make it clear: The war has seriously damaged the American economy, has fueled the flames of inflation, has dried up assets that are extremely necessary to overcome serious domestic problems... and has slowed down the growth rate of profits" (9). In addition, the war has affected the psychology and awareness of many American congressmen about the hopeless goals pursued by the R. Nixon administration. Since the Tet Offensive, this administration has had to continuously face fierce political struggles taking place in the legislative body.

On the diplomatic front, on May 8, 1969, the delegation of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam presented a comprehensive 10-point solution to the South Vietnamese issue. These were the initial fundamental principles preparing the ground for a series of diplomatic agreements aimed at signing a treaty to end the war and restore peace in Vietnam. In joint meetings and private contacts, the delegations from both sides coordinated closely, relentlessly striving to further push the US to de-escalate on key issues, forcing the US to unilaterally withdraw its troops anddeepen internal conflicts among the enemyAt the 21st session, held on June 12, 1969, the South Vietnamese delegation participated for the first time as the negotiating delegation of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam. In response to journalists' questions about this historic event, the spokesperson for the American delegation reiterated Cabot Lodge's words: "Who represents them is their internal affair." This acknowledgment from the American side further disappointed the Saigon government regarding its position in the negotiation process, but due to its heavy dependence on the US, it could not openly oppose the US.

Ms. Nguyen Thi Binh at the signing ceremony of the Paris Agreement on January 27, 1973.

In order to implement its neocolonial policy in South Vietnam, during the initial stages of negotiations, the US consistently avoided discussing the existence of the Saigon government. During the diplomatic struggles of 1971, our delegation persistently demanded the removal of Thieu and, ultimately, the removal of the Nguyen Van Thieu ruling group, prompting H. Kissinger to even consider establishing an independent organization for general elections. This was one of the key issues in the peace talks. By October 1972, with the motto...Winning step by step, we came to a bold, flexible decision “not to demand the removal of the Thieu regime but to maintain the status quo of the two regimes, only agreeing on some major principles such as the two sides in the South will negotiate to resolve internal issues in the South, establish a government structure to supervise and monitor the implementation of the agreement and organize general elections”(10).

That strategic concession by our delegation further deepened the rift in relations between Washington and Saigon. In fact, while reaching that agreement, the American side underestimated Thieu's reaction. They believed that an agreement ensuring the continued existence and legal recognition of the pro-American government would be a significant victory for Thieu, and that other issues would be secondary. However, along with the decision to sign a ceasefire, the American policy of withdrawing troops from the South further weakened the Saigon regime, depriving it of both material and moral support. In a conversation with the US Ambassador to Saigon, Ellsworth Bunker, Thieu lamented: “This is a matter of life and death for South Vietnam and 17 million South Vietnamese people. Our position is very unfortunate. We have been very loyal to the US and now we feel we are being sacrificed... If we accept the document as it is, we will commit suicide” (11). In fact, Thieu sent Bui Diem to Washington to explain to the US side that: “the issue of North Vietnamese troops in the South is a matter of life and death for us. It may be too late now to influence them... But as the proverb says, as long as there is water, we must bail” (12). For its part, in the first months of 1972, the US also vigorously carried out diplomatic activities to “normalize” relations with the Soviet Union, China... and wanted to resolve the “Vietnam problem” and other countries on the Indochina peninsula through the mediation role of some countries (13). But in the end, "Even the Nixon clique had to admit that if they didn't talk to Vietnam, the US had no way out of the deadlock" (14).

Special Advisor Le Duc Tho with a victorious smile at the Paris Conference.

In the Vietnam War, by September 1970, the US had unilaterally withdrawn 140,000 troops. In 1971, the US continued to withdraw troops from the Vietnamese battlefield. This action significantly altered the balance of power. The fighting capacity of the army was severely diminished. Furthermore, the strategic offensive of our armed forces in the spring and summer of 1972 on the Binh Tri Thien and Central Highlands fronts further weakened the enemy. The "Vietnamization of the war" strategy of the Saigon government, with the support of American advisors and modern war equipment, began to show signs of crisis. Regarding the significance of the 1972 offensive, Comrade Le Duan assessed: “Although the victory was limited... but both our position and strength were much better and stronger than before. Most of the main units returned to the South, proactively attacking the enemy in important strategic areas” (15).

To save the situation on the Southern battlefield, R. Nixon mobilized the US military again, restarted the war of destruction in the North, and dropped mines to blockade Hai Phong port and other important ports in order to prevent our supply lines. In September 1972, based on an assessment of the domestic and international situation, the Politburo of our Party decided to take advantage of the opportunity to achieve a diplomatic solution before the US presidential election. On October 4, 1972, the Politburo sent a telegram to the delegation in Paris to temporarily set aside some other demands regarding internal affairs in the South in order to quickly end the war. If we could end the US military involvement in the South, then in the struggle against the puppet regime later, we would have the conditions to achieve those goals and could achieve greater victories (16).

Mr. Le Duc Tho and Mr. Henry Kissinger during the initialing of the Paris Agreement in 1973

Thoroughly grasping the above spirit, closely coordinating with the negotiating delegation, we urgently prepared the Draft Agreement from within the country. On October 8, 1972, on behalf of our Government, advisor Le Duc Tho handed over to H. Kissinger the draft agreement.Draft Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam. In separate meetings, a fierce diplomatic campaign took place on each content and clause of the agreement. By the end of October 1972, "applying Uncle Ho's teachings to negotiations, we came up with an appropriate plan"not simultaneously demanding to resolve the two demands of the US leaving and the puppet regime falling, but focusing on demanding the US leaving first, thereby making the negotiations move quickly from October 1972”(17). At the end of October, the agreement was completed and the two sides agreed to sign it on October 31, 1972, before the US presidential election. Worried that the opposition of the Saigon government could slow down or even disrupt the “peace plan”, from October 19 to 23, 1972, at the request of R. Nixon, Kissinger went to Saigon and delivered to Nguyen Van Thieu R. Nixon’s letter dated October 16 with the commitment: “In the period following the ceasefire, you can be completely assured that we will continue to provide your government with the fullest support, including economic aid and any military aid in accordance with the ceasefire terms of this agreement”(18). However, in Saigon, the Nguyen Van Thieu government reacted strongly to the agreements of its American masters and upon learning the content of the draft agreement, immediately demanded 69 points were corrected (19). Taking advantage of that opportunity, using the excuse of "having difficulties with Thieu," the US side requested our delegation to "further negotiate" and proposed postponing the signing date of the agreement, while committing not to request any further changes after reaching an agreement in this meeting.

Faced with that flippant attitude, in order to gain international public opinion and continue to heighten the political and diplomatic struggle, on October 27, 1972, our Government publicly announced the negotiation situation in Paris and informed the public about the agreement that the parties had reached in October. At the following meeting, along with the request to change some principled contents, H. Kissinger also suggested removing the paragraph: "The United States is not committed to any political tendency or individual in the South, and does not seek to impose a pro-US government in Saigon" (20). Faced with our determined struggle and fear of strong public opposition, on October 26, 1972, H. Kissinger had to declare: "Peace within reach"Because of the ambition to prolong or break the negotiations, the Nguyen Van Thieu government strongly opposed the content of the agreement. The conflict between Washington and Saigon erupted openly. Thieu always felt abandoned by the US in diplomatic agreements. Understanding Thieu's situation, the US side "informed Thieu that disclosing the secret talks at this time would neutralize the growing opposition to the war, help maintain internal US support, and prevent the passage of Congress bills that would harm the Vietnamization program" (21).

Although the US government repeatedly reassured them, in their perception, the Nguyen Van Thieu government still considered it a "surrender agreement". To continue to gain Thieu's trust, on October 29, 1972, the head of the White House affirmed: "But what is more important than what we wrote in the agreement on that issue is what we will do in case the enemy re-invades. I absolutely assure you that if Hanoi does not comply with the conditions of this Agreement, I will resolutely take the fastest and most fierce retaliation" (22). Seemingly unable to rest assured with the commitments, on November 18, 1972, Thieu sent special envoy Nguyen Phu Duc to meet R. Nixon to both present the views of the Republic of Vietnam government and find ways to put pressure back on the US authorities.

In that context, the diplomatic struggle was extremely tense. To pressure us into making concessions, at a private meeting with advisor Le Duc Tho and Minister Xuan Thuy on November 24, 1972, H. Kissinger gave R. Nixon's ultimatum: "Unless the other side shows willingness to pay attention to our reasonable concerns, I instruct you to stop negotiations and we will have to resume military operations until the other side is ready to negotiate on honorable terms" (23). Faced with our principled struggle, the US unilaterally stopped negotiations but did not dare to abandon them, and on the other hand could not reject Thieu's proposals. Unable to easily dismantle the political system of South Vietnam, R. Nixon and H. Kissinger pursued a two-pronged policy: simultaneously appeasing and comforting Thieu while informing him of the strong opposition from many members of the US Congress to the Saigon government's belligerent attitude and protracted war.

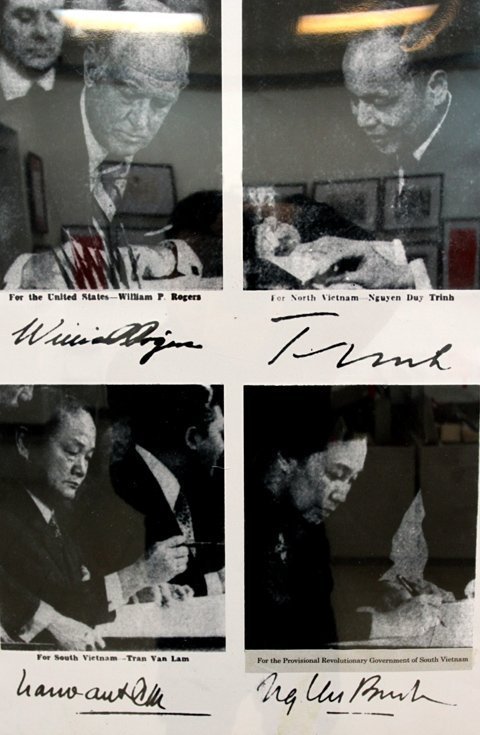

Representatives from the four parties (Democratic Republic of Vietnam; Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam; United States; Republic of Vietnam) signed the Paris Agreement (January 27, 1973).

Faced with the deadlock in negotiations, from December 18 to 29, 1972, in an attempt to use military force to crush our will, the US launched a strategic B-52 raid on Hanoi, Hai Phong and many other cities and densely populated areas, brutally massacring our people. R. Nixon calculated that, internally within the US, the bombing could appease the right-wing faction, preventing them from colluding with Saigon to oppose R. Nixon. The raid also aimed to reassure Thieu about the US's strength, demonstrate the US's commitment, and then pressure Thieu to sign the agreement soon. In addition, "For other allies, the bombing was to demonstrate that the US withdrew from the war as a victor, not surrendering, not abandoning its allies" (24). But the most fundamental and insidious plot was that the US wanted to use military force to exert maximum political and diplomatic pressure on us, forcing Vietnam to accept an agreement under US conditions. After the devastating bombing campaign, Washington also hoped that it could break our fighting spirit and strength, leaving our army and people without enough resources to continue supporting the battlefield in the South and achieving national reunification. However, our army and people staged a decisive battle...Dien Bien Phu in the air" and forced the US to resume negotiations.

By mid-January 1973, the official agreement had been reached between the parties, with its content essentially identical to the draft agreement proposed by the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in October 1972. Recognizing the growing risk of being abandoned by the US, the Nguyen Van Thieu government strongly opposed the peace talks. To quickly overcome the opposition from the Saigon government and to end the war as soon as possible, they focused their efforts on domestic issues, particularly information regarding the incident.WatergateThe situation spread further, and on January 5, 1973, R. Nixon continued to use the "traditional card," which was to both commit to strongly supporting Thieu and threaten: "When we enter the upcoming negotiations, I hope that our two countries will show a united front... If you decide, and I believe that you will decide, to go with us, then I pledge to you that we will continue to support the Republic of Vietnam in the post-reconciliation period and we will respond with full force if North Vietnam violates that reconciliation" (25). On January 17, 1973, in a letter to Nguyen Van Thieu, the US President continued to declare: “I would like to reiterate what I have said to you in my previous letters: The freedom and independence of the Republic of Vietnam remains a supreme goal of US foreign policy... I would like to once again declare the commitments in this letter: First, we recognize only your government as the sole legitimate government in Vietnam; Second, we do not recognize the right of foreign troops to remain in the South of Vietnam; Third, the United States will have strong reactions to violations of the agreement” (26).

These are just a few excerpts from 27 letters and messages that R. Nixon sent to the Thieu government over the three years leading up to his resignation on August 9, 1974, due to the incident.WatergateAlthough the content of those letters covered many issues, there was always a fundamental message: the United States was committed to providing comprehensive support to the Republic of Vietnam in political, military, and economic terms. However, these commitments were largely alien to historical reality, especially the content of the agreement that the Nguyen Van Thieu government had to accept. In the Saigon government's perception, the Paris Agreement, consisting of 9 chapters and 23 articles, could effectively be considered a death sentence, particularly Article 3b and Article 5 of Chapter II.

Noticing the hesitant attitude of Nguyen Van Thieu's group, on January 19, 1973, R. Nixon sent Thieu another letter forwarded by General Alexander Haig. In it, he informed Thieu: "I have definitively decided to initial the agreement on January 23, 1973 in Paris. If necessary, I will do so alone" (27). In subsequent meetings, A. Haig even told Nguyen Van Thieu and Hoang Duc Nha: "If we do not sign the agreement, the United States will take brutal measures." Immediately, both understood the "historical significance" of that statement, which referred to the events of 1963. With no other choice, Nguyen Van Thieu had to accept and only asked to propose minor amendments. On January 20, 1973, the day R. Nixon entered the White House for his second term, the US side again pledged to the Nguyen Van Thieu government: "The United States recognizes your government as the only legitimate government in Vietnam" and at the same time requested Thieu to accept the content of the agreement and give his opinion no later than 12 noon on January 21, 1973. In fact, it can be considered an ultimatum from the R. Nixon government to the Saigon puppet government. In Paris, only 2 days later, Kissinger initialed the document and exactly 4 days later, on January 27, 1973, the Saigon government also had to sign the agreement. In his speech on radio and television on January 23, 1973, the US President said: "An honorable peace has been achieved" (Peace with Honor)(28). But, for the Nguyen Van Thieu group, it was truly “A bitter peace”(A Bitter Peace(29). And what R.Nixon believes, with the agreement, the Republic of Vietnam has gained a precious right, namely the "right to decide its own future" (30) is in fact an abandonment, a merciless shedding of "responsibility". Thus, as Westmoreland, former Commander-in-Chief of the US military in South Vietnam, admitted: "The fate of South Vietnam was sealed when Kissinger signed the ceasefire agreement, withdrew US troops and allowed thousands of North Vietnamese regular soldiers to remain in the South" (31). It should also be added that, when asked by Ehrlichman, one of R.Nixon's assistants: "How long do you think South Vietnam will last with this agreement?" H.Kissinger replied: "I think if they are lucky, they can hold out for a year and a half" (32).

Thus, after repeatedly going against its commitments, the United States was forced to make a final, written commitment to ending the war in Vietnam. For us, the strategic objective of signing the Paris Agreement was fully achieved. Because, along with forcing the United States and other parties involved to recognize our independence, sovereignty, unity, and territorial integrity, "the important thing about the Paris Agreement was not the recognition of two governments, two armies, two zones of control, and the establishment of a three-component government, butThe key point is that the American troops must withdraw while our troops remain.The North-South corridor was still connected, the rear was linked with the front to form a unified continuous strip; our offensive position was still stable.Our intention is to maintain our position and strength in the South in order to continue our offensive against the enemy.”(33). These are the two greatest victories of Vietnamese diplomacy and Vietnamese intelligence in the process of signing the Paris Agreement.

3. The end of the war and the fate of the Saigon government

President of the Republic of Vietnam Nguyen Van Thieu announced his resignation on April 21, 1975.

In the early 1970s, due to the impact of the oil crisis, the economies of the capitalist world, including the United States, fell into a serious recession. Under intense domestic pressure over the issue of American soldiers being killed and captured in the "Vietnam War" as well as the increasingly widespread anti-war movement around the world, along with the southern battlefield, the United States had to withdraw its troops from Thailand and gradually reduce aid to its vassal states.

Despite his disappointment with the Saigon political system and the weak combat capabilities of the puppet army, Washington still harbored ambitions to maintain the puppet regime of Nguyen Van Thieu in South Vietnam. Along with the 8-year post-war economic plan (1973-1980) aimed at making the South's economy superior to that of the socialist North, in terms of politics and military affairs, "The consistent plot of the US in South Vietnam was to continue using the Saigon puppet regime as a tool to implement neo-colonialism, to find every way to eliminate the liberated areas and our people's armed forces, to abolish the people's government, to turn the South into a separate pro-American nation, receiving US military, economic, and financial aid so that the US could cling to the South for a long time and avoid the risk of directly participating in a large-scale war" (34).

In order to strengthen the puppet army, from October 1972, on the one hand, the US made promises and commitments in Paris, on the other hand, it carried out the plan "Enhance Plus"The US established an airlift and massively supplied weapons and war equipment to the Saigon government. Within two months, the White House sent 260,000 tons of war equipment worth nearly $2 billion to Vietnam. Relying on US aid and advice, the Saigon regime prepared the 'Ly Thuong Kiet Plan,' implementing the 'Territorial Inundation' campaign to win over the population and seize land. Even as the Paris Agreement was about to be signed, the Nguyen Van Thieu government still ordered troops to occupy Cua Viet port (Quang Tri) and many other areas. However, these armed actions could not conceal their weakness on the battlefield. Based on strategic analysis, after signing the Paris Agreement, the Central Committee of our Party concluded: Once the US withdrew its troops from South Vietnam, it was unlikely they would return. However, even if they intervened to some extent, it would not change the war situation."

During the protracted Paris negotiations, on the battlefields of South Vietnam, the US transferred most of its military bases to the Saigon government. By 1973, the total number of South Vietnamese troops had reached 1.1 million, accounting for 50% of the youth aged 18 to 35. The Pentagon also continuously strengthened the air force and heavy artillery of the South Vietnamese regime. “Starting with only 75 old-model helicopters in 1968, the Republic of Vietnam had 657 of the latest model by July 1972. This gave the Republic of Vietnam one of the largest and most modern helicopter fleets in the world. In addition, the air force, consisting of 740 aircraft, was the fourth largest in the world. In 1971, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam received at least 1,000 artillery pieces, 1,650 heavy mortars, over 1,000 M.113 personnel carriers, 300 tanks, and an advanced communications system to tie that disparate army together. The amount of equipment that army received is a mystery because after the US withdrawal, the US left behind a huge amount of material” (35). Pursuing a neo-colonial policy with the basic plot of maintaining the existence of the Saigon puppet government and permanently dividing our country, the US also changed the names of many military agencies to civilian ones while still maintaining 24,000 military advisors and civilian staff in the South.

On April 3 and 4, 1973, Nguyen Van Thieu went to the United States to meet President R. Nixon in San Clemente. At the meeting, R. Nixon pledged to continue military support for the Saigon government. Immediately after that, the United States resumed reconnaissance flights over the skies of North Vietnam and suspended meetings of the Joint Economic Committee on rebuilding North Vietnam. In May 1973, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Vietnamese Workers' Party stated: "The US imperialists continue to maintain a certain military commitment and continue to help the Saigon puppet regime so that its lackeys can stand firm and deal with the North, while ensuring that the US can stay in the South for a long time, avoiding the risk of having to directly get involved in a new war in the South" (36). The United States condoned and, together with the Saigon government, systematically sabotaged the Paris Agreement. From February 1973 to mid-1974, under the command of American advisors, the puppet army organized 34,266 large-scale attacks to occupy liberated areas and 216,000 pacification operations in controlled areas.

The puppet regime evacuated and fled Saigon on April 30, 1975.

But by 1974, the political and economic situation in the US had become increasingly unstable. Among the many reasons, theWatergatehas plunged American politics into a serious scandal.Watergateis considered the most vicious political corruption in American history. This scandal caused a profound crisis of power that made R. Nixon unable to save his honor and eventually had to resign as president. R. Nixon's political failure caused the Nguyen Van Thieu government to lose its last reliable support under the umbrella of American patronage. The relationship between Washington and Saigon from then on fell into a state of crisis and serious distrust. However, to reassure and maintain "honor" with its allies, less than 24 hours after succeeding R. Nixon, the new US President Gerald Ford sent a message to Thieu and affirmed: "The commitments that our country promised to your country in the past are still valid and will be fully respected during my term. These commitments of mine are particularly suitable for the Republic of Vietnam in the current conditions" (37).

In fact, the political situation in the United States did not allow the G. Ford administration to continue maintaining a high level of aid to the puppet regime. From January 2, 1973, the US House of Representatives and Senate passed a resolution to cut all funding for any US military operations in Indochina except for a limited budget for troop withdrawal and prisoner repatriation. In the precarious situation of the South Vietnamese government, in June 1974, General John Murray cabled the Pentagon: “If aid is still at $750 million, Saigon will only be able to defend a portion of the land. If it goes down further, it means eliminating the Republic of Vietnam” (38). In the report of the puppet General Staff to Nguyen Van Thieu in 1975, it was also clearly indicated the “vital importance” of US aid: “If the US provides $1.4 billion in aid, Saigon will control the whole South; with $1.1 billion, Saigon will lose half of Military Region I in the North; if only $900 million, it will lose the entire Military Region I and Military Region II; if only $600 million, it will only control half of Military Region III from Bien Hoa to Military Region IV” (39). In reality, US aid to the Saigon government decreased from $2.27 billion in 1973 to $1.03 billion in 1974 and $1.45 billion in 1975.

In parallel with the diplomatic struggle, to prevent the US and the Saigon government from constantly violating the terms signed in the Agreement, our armed forces mastered the strategic offensive position, defeating the encroachment operations of the Saigon army. In July 1973, the Central Executive Committee of the Vietnam Workers' Party issued Resolution XXI, continuingaffirming the path of revolutionary violenceThe policy was to intensify the struggle on three fronts: military, political, and diplomatic, while proactively preparing for the possibility of waging revolutionary war across the Southern battlefield.

From the battlefield reality and analysis of the international political situation, realizing that some countries with ambitions to intervene in the Vietnam issue could not immediately implement specific measures and that the US was unlikely to send troops back to Vietnam, from September 30 to October 8, 1974, the Politburo met to discuss the policy of liberating the South and made the assessment: “At this time we have the opportunity... This is the most favorable opportunity for our people to completely liberate the South, achieve complete victory for the national, democratic revolution and at the same time help Laos and Cambodia complete the cause of national liberation” (40). After the second meeting from December 8, 1974 to January 8, 1975, the Politburo set forth the strategic determination to completely liberate the South in the two years 1975-1976, and then after successive victories, graspingA new strategic opportunityOn March 25, 1975, the Politburo and the Central Military Commission once again resolved to liberate South Vietnam.before the rainy season1975(41).

On January 6, 1975, when Phuoc Long province was liberated, to reassure public opinion, US Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger still stated: "This is not yet a massive offensive by North Vietnam" (42). By January 22, 1975, in the face of rapid developments on the battlefield in South Vietnam, President G. Ford still declared: "There will be no other action than to supplement aid to Saigon. The United States will not intervene without constitutional and legislative procedures" (43). But, after Phuoc Long, the Central Highlands campaign, whose decisive opening victory was Buon Ma Thuot on March 11, opened a new phase for our country's revolution. On March 21, we launched the Hue - Da Nang campaign. On March 25, 1975, Thieu wrote a long letter to G. Ford with urgent words:

"As I write this letter to you, the military situation in South Vietnam is extremely urgent and worsening with each passing hour...

In accordance with the firm commitments made at the time, we were promised that the United States would retaliate swiftly and forcefully against any violation of the agreement by the enemy.

We regarded those commitments as the most important guarantee of the ceasefire agreement. We believed those commitments were crucial to our survival.

Mr. President,

In this moment of utmost urgency, when the very life of the free South is in peril and peace is seriously threatened, I solemnly request that you take the following two necessary measures:

- Ordered B-52 aircraft to drop bombs in a short but intense period on enemy troop concentrations and logistical bases in South Vietnam, and

- Provide us with the necessary means to stop and repel the attack.

...

Mr. President,

Once again, I wish to appeal to you, to the credibility of U.S. foreign policy, and above all, to the conscience of the American people.”(44)

The Vietnamese Liberation Army entered and liberated the Independence Palace on April 30, 1975.

In its desperation, to ensure its own survival, the Nguyen Van Thieu regime revealed its reactionary nature, acting against the national interest. G. Ford received letters from Thieu and appeals for help from the Presidents of the Senate and House of Representatives of the Republic of Vietnam, but received no response. He also decided to keep those letters without informing the government or the two houses. Unable to continue down the dead-end tunnel of the "Vietnam War" and enduring the pressure of anti-war protests from multiple sides, G. Ford boarded a plane to take a vacation in Palm Springs. Just four days later, Da Nang, the largest military coalition in Central Vietnam under the Saigon regime, fell. The path to Saigon for our army was now wide open. On April 16, G. Ford ordered the evacuation of Americans from Saigon and simultaneously sent an urgent letter to Leonid Brezhnev, requesting that the Soviet leadership lobby Vietnam to allow the Americans to carry out the evacuation from South Vietnam. The fate of the Saigon government could only be counted day by day. However, some factions within the Saigon government still hoped to reach a "peaceful solution" and that the US could mobilize B-52s for carpet bombing, halting the rapid advance of our army.

Two days after Nguyen Van Thieu resigned, realizing that the political fate of the South Vietnamese government was irretrievable, on April 23, 1975, at the University of New Orleans, US President Gerald Ford had to admit in despair: “The war in Vietnam is over for America. America can no longer help the Vietnamese people; they must face whatever fate awaits them” (45).

And on April 30, 1975, when our main army corps advanced to liberate Saigon, for the sake of "honor" and the interests of the United States, the Washington authorities abandoned the Saigon puppet regime, just as they had abandoned the Lon Nol regime on April 17, 1975. Due to various reasons, in the final years of the "Vietnam War," in order to maintain American influence and save the Saigon puppet regime, the US repeatedly made commitments that contradicted those commitments. Historical reality shows that, despite its powerful military and economic potential, the US could not always fulfill its promises to its "allies."

During that process, as H. Kissinger acknowledged, US diplomacy “was damaged and needed time to regain its balance.” According to his justification, by failing to maintain its position, the United States had to “go from one concession to another while North Vietnam did not change its diplomatic goals but only made insignificant changes to its diplomatic position” (46). The final result was, before the iron resolve “Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom."Our nation's strength, by knowing how to combine national strength with the strength of the times, seizing the right revolutionary opportunity, thoroughly exploiting contradictions within the enemy's ranks, and ending the war at the right time..., our army and people defeated the 'Vietnamization of the war' strategy, brought down the pro-American puppet regime in South Vietnam, liberated the South, and unified the country."

Note

1. The Communist Party of Vietnam:Complete Collection of Party Documents, National Political Publishing House, Hanoi, 2004, Volume 28, p. 174.

2. NewspaperPeopleJanuary 28, 1967.

3. Trinh Ngoc Thai:President Ho Chi Minh and the Paris Conference; within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:The diplomatic front with the Paris negotiations on Vietnam., National Political Publishing House, Hanoi, 2004, p. 78

4.Pentagon documentsGravel Edition, Volume 4, p. 206.

5. Luu Van Loi:Vietnamese diplomacy(1945-1995), People's Police Publishing House, 2004, pp.228-229.

6. Larry Berman:No Peace, No Honor - Nixon, Kissinger, and Betrayal in Vietnam, Published by Simon & Schuter, New York, 2002, p.14.

7. Larry Berman:No Peace, No Honor..., p.14.

8. Quoted from Luu Van Loi:Vietnamese diplomacy(1945-1995), Ibid., p. 242.

9. Gabriel Kolko:Anatomy of a War, People's Army Publishing House, Hanoi, 2003, p. 388.

10. Luu Van Loi:Kissinger faced Le Duc Tho.; within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:Diplomatic front..., Ibid, p. 114.

11.New York TimesSunday, April 30, 2000.

12. AJLangguth:Our Vietnam - The War 1945-1975, Simon & Schuster Publishers, 2000; cited by Luu Doan Huynh:Why did the United States use B-52s before signing the agreement??; in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:Diplomatic front..., Ibid., p. 213.

13. Kit-Singe:The top-secret meeting minutes have not yet been released., Thanh Nien Publishing House, Hanoi, 2002.

14. Le Duan:Letter to the South, Truth Publishing House, Hanoi, 1985, p. 280.

15. Le Duan:Letter to the South, Ibid, p. 302.

16. Doan Huyen:Defeating America: Fight and Negotiate, in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:Diplomatic front..., Ibid, p. 141.

17. Nguyen Thanh Le:Looking back at the Paris negotiations on Vietnam; within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:Diplomatic front..., Ibid, p. 403.

18. Quoted from Nguyen Tien Hung - Jerrold L. Schecter:Secret files of the Independence Palace(The Palace File), Harper & Row Publishers, Los Angeles, 1987, p.1.

19. Regarding this matter, Hoang Duc Nha, former "Secretary to the President, Minister of National Mobilization and Repatriation" of the Republic of Vietnam, wrote: "Even during the period from October 12 to 17, 1972, Mr. Kissinger and Le Duc Tho agreed on an agreement that the Republic of Vietnam had not yet been informed of. They believed that South Vietnam would not cause difficulties: the North Vietnamese communists believed their own propaganda that the Republic of Vietnam would not resist the United States, while the United States believed that since the communists no longer demanded the President of the Republic of Vietnam resign before peace was achieved, he would agree to sign this agreement"; See Larry Berman:No Peace, No Honor - Nixon, Kissinger, and the Betrayal in Vietnam, published by Viet Tide, 2003, pp. 16-17No Peace, No Honor - Nixon, Kissinger, and Betrayal in Vietnam, Published by Simon & Schuter, New York, 2002).

20. Quoted from Luu Van Loi:Vietnamese diplomacy(1945-1995), Ibid., p. 304

21. Larry Berman:No peace, no honor..., op. cit., p. 163. Speaking on television on the occasion of the initialing of the Paris Agreement, R. Nixon also reiterated this view.

22. Nguyen Tien Hung - Jerrold L.Schecter:Secret files of the Independence Palace, Ibid, p.2.

23. Luu Van Loi:Vietnamese diplomacy(1945-1995), Ibid., p. 305

24. Luu Doan Huynh:Why did the United States use B-52s before signing the agreement??; in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:Diplomatic front..., Ibid., p. 215.

25. Nguyen Tien Hung - Jerrold L.Schecter:Secret files of the Independence Palace, Ibid, p.2.

26. Nguyen Tien Hung - Jerrold L.Schecter:Secret files of the Independence Palace, Ibid, p.4.

27. Quoted from Luu Van Loi:Vietnamese diplomacy(1945-1995), ibid, p.318

28. Larry Berman:No Peace, No Honor...p.286.

29. Pierre Asselli:A Bitter Peace - Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement, The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

30. Larry Berman:No Peace, No Honor...p.286.

31. Dinh Nho Liem:The significance of victory and some lessons learned.; within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs:Diplomatic front..., Ibid, p. 416.

32. Larry Berman:No Peace, No Honor...p.8.

33. Le Duan:Letter to the South, Ibid, pp. 359-360.

34. Le Duan:Letter to the South, Ibid, p.334.

35. Gabriel Kolko:Anatomy of a War, Ibid, p.437.

36. Communist Party of Vietnam:Complete Collection of Party DocumentsVolume 34, p. 177.

37. Quoted from Nguyen Tien Hung - Jerrold L. Schecter:Secret files of the Independence Palace, Ibid, pp. 403-404.

38.History of the Communist Party of Vietnam, National Political Publishing House, Hanoi, 1995, Volume 2, p. 599.

39. Hoang Van Thai:The decisive years, People's Army Publishing House, Hanoi, 1985, p. 140.

40. Le Duan:Letter to the South, Ibid, pp. 360-362

41. Van Tien Dung:The Great Victory of Spring, People's Army Publishing House, 2003, p. 124

42.History of the Communist Party of Vietnam, Ibid, Volume 2, p. 650.

43. Ministry of Foreign Affairs:The diplomatic front with the Paris negotiations on Vietnam., Ibid, p. 543

44. Quoted from Nguyen Tien Hung - Jerrold L. Schecter:Secret files of the Independence Palace, Ibid, pp. 5-6.

45.History of the Communist Party of Vietnam, Ibid, Volume 2, p. 713.

46. Ministry of Foreign Affairs:The diplomatic front with the Paris negotiations on Vietnam., Ibid, p. 548.

Author:Prof. Dr. Nguyen Van Kim

Newer news

Older news