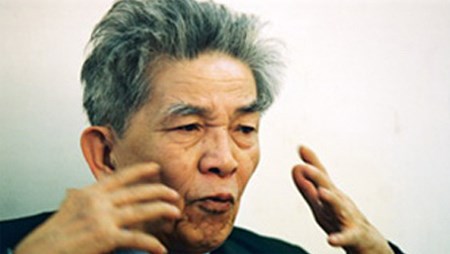

Professor, Doctor, People's Teacher Nguyen Tai Can (1926-2011)

This year (1996), my teacher, Professor Nguyen Tai Can, is seventy years old. I wanted to write a few lines as a token of gratitude from his student. But I find it so difficult!

My teacher was a man of vast learning and great talent, but a small page could only convey a few thoughts. Moreover, he was a very upright man, deeply ingrained with Confucianism (in the words of Professor Phan Ngoc), unwilling to be spoken of by others, and unwilling to speak of the word "self" himself.

Back when I was in high school, one of my teachers – Professor Vu Ngoc Khanh – once criticized me for not knowing how to present information on the blackboard, saying:I have a friend named Nguyen Tai Can, a very talented man with beautiful handwriting, unmatched by anyone in his blackboard writing. If you could learn from him, you would gain a lot."Another time, Mr. Dang Van Dai, my teacher in junior high school, told my father: 'Mr. Nguyen Tai Can has just passed the doctoral examination (later called Associate Doctorate) in the Soviet Union along with Mr. Nguyen Canh Toan.'"

My father was happy and explained to me:Uncle Can was the former head of the Editorial Department under my father at the Education Department of Inter-Region 4 back then; he was a very capable person."

Then, a few years later, I entered the Faculty of Literature at Hanoi University. At the end of the summer of my second year (1962), along the road lined with flamboyant trees in the Faculty of Literature's dormitory in Lang village, I saw a man wearing a fedora hat, sunglasses, and a suit, pushing his motorbike into the faculty.

The students whispered to each other:That's Teacher Nguyen Tai Can.!" My memories awakened, coupled with the curiosity of youth, and I cautiously approached him, but I didn't learn anything more.

A few days later, I was extremely surprised to see him, dressed very simply, sitting and smoking a pipe at a tea stall near the school gate, looking very relaxed, while the upperclassmen crowded around him, laughing and chatting happily with their teacher… and then, by chance, for the past 35 years, I have lived and worked alongside him, guiding many generations, including myself, to grow together with the development of Vietnamese linguistics.

Professor Nguyen Tai Can's scientific spirit can be summarized in eight words:Profound - Wise - Talented - Strict"Each word only needs one example. With his successful description of Vietnamese noun phrases, going so far as to sometimes consider "word class" as the central element, he redefined the entire system of describing Vietnamese grammatical structure (1960). By correctly placing the linguistic position of "sound one"In our language," he affirmed the overarching influence of this "isolated" characteristic on the Vietnamese language (1960). These ideas are very profound and have today become the basic content of scientific discussions about the Vietnamese language.

As a learned man, he possessed a thorough understanding of linguistics, Sino-Vietnamese studies, historical linguistics, and various fields of Vietnamese linguistics. His body of work was vast, and he delved deeply into every area. He understood both ancient and modern linguistics, quickly grasping issues in contemporary linguistics while simultaneously discussing and proposing unique ideas on classical linguistics.

Professor Cẩn was also a talented man, full of poetic inspiration, composing poems quickly and beautifully, especially in classical Chinese. His collected poems certainly place him among the last classical Chinese poets of this century. In the lecture hall of the Vietnamese Studies department at Paris 7 University, there is a pair of couplets in Nôm script on faded red paper, beautifully written, urging students to study hard. These couplets were a gift from Professor Nguyễn Tài Cẩn to the department; the first time I saw them, I was reminded of an old poem by Yến Lan:

"When my teacher came for the first lesson,

An old bookcase, with a brown screen.

A pair of paper couplets with dragon and butterfly motifs.

"The long, squishy teeth follow the lines of the Chinese ink.".

Professor Vu Duc Nghieu, from my department, told me that the Southeast Asian Studies department at Cornell University in the United States also displays another Nôm couplet by the professor, containing advice for his students, which he gifted when he visited to give lectures there.

Speaking of the teacher's talent, one must also mention his exceptionally skillful teaching methods. He conveyed extremely abstract concepts to students in a very concrete, vivid way, sometimes infused with wit and colloquialisms, leaving a lasting impression.

There are many stories about the professor's strictness in his work. Being close to him, I was often scolded and given sincere advice. One funny story: once, a student working on a thesis with him disappeared because he didn't follow the professor's instructions. A short time later, facing graduation exams, the student had to go see the professor. He brought tea and cigarettes as a token of gratitude. The professor accepted them immediately, but then insisted that the student stay at his house, eat meals, and write until the thesis was completed.

Many anecdotes exist about Professor Nguyen Tai Can, but above all, his dedication to building the field of Vietnamese linguistics is paramount. Throughout his life, he focused on one goal: training and developing the academic community, building a professional and modern system that remained relevant to the Vietnamese context. He was deeply saddened by the professional work he couldn't accomplish. Professor Hoang Trong Phien once said: "Professor Nguyen Tai Can breathed new life into our field, trained countless students for Vietnamese linguistics, and deserves the highest honors in science."

My teacher lived a simple life, so simple it was almost austere, even though he lacked nothing. Whether at home or abroad, he always maintained a distinctive style that he often described as "of a person from Nghe An."

On the occasion of his 70th birthday, far from home, I remembered my teacher and on a cold, snowy winter night I wrote a few clumsy verses of classical poetry to send to him back home:

"Before we knew it, my teacher was seventy years old.

Through the long years, filled with both joy and sorrow,

A lifetime of teaching to cultivate a pure heart.

Three steps through the hardships of life, and the night will never be calm.

Students of all ages held him in high esteem.

Friends near and far extend their warmest greetings.

Tea poured in the new year, sad stories of the past²

Those born in the year of the Tiger (1966) will never lose their faith."

(Québec, 1995)

Since his retirement, my teacher has written and published three books. All are reflections of a lifetime, their titles sounding complex: "Historical Phonetics of the Vietnamese Language," "Classical Chinese Literature of the Ly and Tran Dynasties,"... Now he is nearing completion of "Ancient Chinese-Vietnamese," and plans to continue writing about Chinese in regional countries, and create a Vietnamese etymological dictionary (already completed up to the letter C). It all began with a literary suggestion from scholar Hoang Xuan Han more than ten years prior: whether it was possible to use the taboo words in the original Tale of Kieu to understand its history through its various stages. My teacher pondered, toiled, and decided to tackle a problem no one had yet addressed: applying the methods of historical linguistics to textual research. He started with the Duy Minh Thi version of the Tale of Kieu (1872). A massive body of research has been published. Then came the major book researching 19th-century Nôm texts of the Tale of Kieu. By continuing his research on taboo words in the story, the professor boldly became the first to propose a new timeframe for Nguyen Du's composition: when the poet was just over thirty years old (1787-1790). His recent groundbreaking articles have stirred up debate among classical scholars regarding his bold and scientifically grounded new ideas.

When you were 70 years old, I respectfully wrote you a few verses from afar; now that you are 80 (2006), again from afar, I would like to send you a few more verses in response:

Before we knew it, our teacher was eighty years old.

My mental and physical energy never rested throughout the months and days.

Ten years and six books brought him fame and fortune.

Before long, thousands of pages would become mere trifles.

The teacher sets a good example for the younger generation.

The student was exhausted from learning from the teacher.

The teacher is healthy, happy, and so fortunate!

Friends and disciples everywhere.

Seoul, May 2005

After writing it in Seoul, I sent it to him on his birthday. A few days later, I received a very touching letter from him, along with his reply:

"Eighty is not yet a hundred.

There are many more wishes for longevity, year after year.

Still practicing Yoga: following Taoist principles,

Regular relaxation: practicing meditation.

Just like Zhuangzi: enjoying the life of a butterfly,

Still learning from the Foolish Old Man: Extracting the silkworm's intestines.

Living here, dying here depends on fate and fortune.

"This is my way of thanking my kindred spirit."

Moscow, June 2005

My professor's consistent academic success stemmed from his very modern and sound thinking method. He had a firm grasp of linguistic theories in various historical contexts. Bold yet cautious, he successfully applied linguistic theories to native-language materials, both modern and historical, opening up many new ideas.

This reminds me of two stories about the teacher.

Professor Keith Taylor, a renowned Vietnamese studies scholar in the US specializing in Vietnamese language and the history of the Ly-Tran dynasties, requested to take a course in Nom script with Professor Taylor. He recounted his surprise after the course, describing a brilliant, friendly, yet very serious Vietnamese scholar with a unique teaching method – highly linguistic but practical and remarkably effective. He learned nearly 500 of the most commonly used Nom characters and even learned how to read texts using them, all within a short period of diligent study.

On another occasion, a professor at Hanoi Pedagogical University who taught Vietnamese literature introduced an American student to her to learn about the language of Vietnamese folk songs. The student was proficient in Vietnamese and expected the professor to give him some lectures and illustrations to take notes on. However, the professor didn't do that. Instead, the professor tested his Vietnamese, explained the linguistic principles of folk songs, introduced some techniques for composing them, and then assigned him homework to practice writing folk songs at home, with the requirement to bring them back after a week for correction. It was very difficult at first, but with persistent practice, he eventually succeeded. The professor praised and corrected his work until he understood the basics through practice before explaining the theory. The professor recounted that the student had once managed to write several verses:

"I've been in Hanoi for a long time,

Knowing Hoan Kiem Lake, knowing Chuong Duong Bridge,

Explore the thirty-six streets and alleys.

It felt like I was rediscovering my second home.

The teacher said that although it wasn't perfect, it followed the rules, which was commendable and worthy of respect.

Not long ago, there was good news. This year (2000), the State awarded the second Ho Chi Minh Science Prize to outstanding scientific works of our country. Professor Nguyen Tai Can's work, "Problems of Vietnamese Grammar and History," was one of the very few scientific works from the Literature and Linguistics field that passed four rigorous rounds of voting by the national scientific community before being submitted to the State. Professor Can was abroad at the time, so I sent him an email to inform him. A few days later, I received a letter from him. He was happy to have earned the trust of his colleagues, but immediately told me that I had to focus on my work before thinking about praise. Two years earlier, he had been awarded the First Class Labor Medal by the State. He was away at the time, but upon his return, he emotionally told his colleagues in the Party branch: "I have followed the Party for over 50 years, and I must always strive to be an honest and consistent Communist."

Knowing that he was such a serious and insightful researcher, in 1985, when Professor Nguyen Dong Chi, Vice Director of the Institute of Han Nom Studies, passed away, Professor Nguyen Khanh Toan offered him the position of Director, but he considered it and declined. Instead, he introduced one of his students to join the Institute's leadership board. My professor confided in me: "I wouldn't dare criticize the good intentions of my superiors, but after much consideration, I can't accept it, Duc. Experience shows that I'm passionate about science and professionalizing activities. When I take on any task in scientific management, I immediately think about proposing new ideas, seeking international contact to find information, improving working methods, and standardizing operations. But doing that here isn't feasible because it would affect personnel and the interests of others, and cause trouble. We are inherently perfectionists who are content with the status quo, so we are often hesitant to change. If we try to innovate, it's easy to cause conflict and may even bring misfortune. So I think, let's just focus on doing science well according to our strengths. From now until the end of my life, I will strive to follow that path for as long as God allows me to live; that will be more peaceful and also more reasonable." These were the heartfelt words my professor expressed just before the Doi Moi (Renovation) period.

Spring of 2009. After the Lunar New Year, I and Mr. Le Quang Thiem visited our teacher to say goodbye before he went to Russia to be with his family. We chatted all afternoon, drinking tea and talking about all sorts of things. Our teacher was happy. At the end of the day, he asked us to stay for dinner, but Mr. Thiem and I excused ourselves so he could rest. He saw us off to the yard. Spring had arrived, and a peach tree in his yard was blooming beautifully. As we stood under the tree's shade, for some reason, our teacher suddenly embraced each of us and kissed us affectionately. We were deeply moved. We also didn't realize that it would be the last time he would hug us before leaving us forever.

This year marks the first anniversary of my teacher's death. I brought a bottle of corn wine from Moc Chau to offer as a tribute. We stood under the peach tree again, the same one from last year. The peach blossoms were in full bloom once more. On the twenty-third day of the first lunar month, after Tet (Lunar New Year), I stood under the tree, my heart filled with nostalgia for my teacher, and I found myself drawn to a line from Vu Dinh Lien's poem:

The peach blossoms are blooming again this year.

The old scholar was nowhere to be seen.

People of the olden days

Where is the soul now?

My teacher has passed away, but his spirit remains here, beside us, his students who are neither particularly talented nor intelligent, but who, thanks to his guidance and care over half a century, have achieved a certain degree of maturity.

Quebec, 1995 - Hanoi 2012

PROFESSOR, DOCTOR, PEOPLE'S TEACHER NGUYEN TAI CAN

+ Workplace: Faculty of Literature (Hanoi University). + Management position: Head of the Linguistics Department (Faculty of Literature) (1961-1971).

Nouns are a word class in modern Vietnamese.i, Social Sciences Publishing House, 1975. Vietnamese Grammar: Words - Compound Words - PhrasesUniversity and Vocational High School Publishing House, 1975, National University Publishing House (reprinted many times). The origin and formation process of Sino-Vietnamese pronunciationSocial Sciences Publishing House, 1979, National University Publishing House (reprinted many times). Some issues concerning the Nôm script.University and Vocational High School Publishing House, 1985. A textbook on the history of Vietnamese phonetics (preliminary draft).Education Publishing House, 1995. The influence of Chinese literature during the Ly and Tran dynasties through the poetry and poetic language of Nguyen Trung Ngan.Education Publishing House, 1998. Explore the technique of sequential rhyming in Thieu Tri's poem "Vu Trung Son Thuy".Thuan Hoa Publishing House, 1998. Some evidence related to language, writing, and culture.National University Publishing House, 2001. Documents on the Tale of Kieu: Duy Minh Thi Edition 1872National University Publishing House, 2002. Documents on the Tale of Kieu: From the Duy Minh Thi edition to the Kieu Oanh Mau edition.Center for National Studies. Literature Publishing House, 2004.

+ Ho Chi Minh Prize for Science and Technology in 2000 for a series of works on Vietnamese grammar and history, includingVietnamese Grammar; Textbook on the History of Vietnamese Phonetics;The origin and development process of Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation.. |

Author:Professor, Doctor, People's Teacher Dinh Van Duc

Newer news

Older news