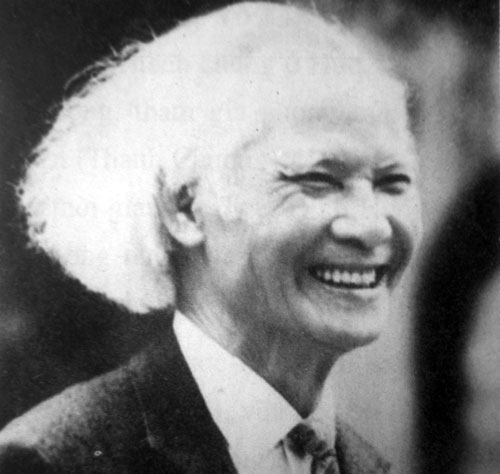

Associate Professor and Meritorious Teacher Tran Dinh Huou (1926 - 1995)

1. I was running frantically on the football field when Professor Tran Ngoc Vuong waved me over. “Vi, come with me to Gia Lam tomorrow morning. I’m so anxious. Mr. Huou’s house is leaking, all the books are soaked. They’re all precious books. I’ve borrowed Tuan’s (poet Do Minh Tuan) bicycle. Can we get there?”

It was the winter of 1974. We left the Me Tri dormitory at 5 a.m. Our rickety bicycle carried us along the foggy road across the Long Bien bridge. We took turns pedaling. The left bank of the Red River meandered endlessly under low, gloomy clouds. The sky in my hometown was rarely this heavy. After passing Chau Quy, we came to a truly dilapidated thatched house, nestled beside another house's garden. The house was very similar to the three-room house I lived in during the 1966 American bombing raid. I had studied with teachers whose lives were interwoven with endless evacuations. The teachers held up the curtains to greet us. A row of bookshelves, some made of bamboo, some of rough planks, sagged down, covered with mats and burlap sacks. The elegant spines of Russian books peeked out. I looked up. It wasn't just leaking. The rafters and bamboo strips were broken and pushed aside. The thatched roof had crumbled in chunks. Looking through the window, I asked, "Whose bamboo clump is that? Can we have a few?" “Okay! We’re all relatives.” “Is there any straw in the village? Could you go ask for a few bundles for me?” “But how?” “We can’t starve anymore, sir. We’ll just re-roof. I can do it.” Slightly skeptical, the teacher asked her to go ask for straw. I took my knife, rushed to the bamboo grove, and cut three bamboo stalks, bringing them into the yard. Two old stalks were split into rafters, and one was a young, thin stalk. Then, I climbed onto the roof and threw all the old straw down, asking Mr. Vuong to gather it into a pile for reuse. It turned out that people in the north build their houses very haphazardly, not as carefully as in our storm-prone countryside. The roof was soon sparkling clean. Looking down, I saw the teacher pacing back and forth, looking worried. Mr. Vuong took one room, I took another, quickly tying bamboo strips together in rows. “Tile houses are sturdy, thatched houses are made of strips,” once tied, it was stable, and we could walk on the roof without worry. The straw had also just been obtained. I used the straw to build the roof in sections, prioritizing fresh straw for the outer room, where the bed and bookshelf were. By noon, the back roof had reached the gable. We climbed down to eat. Sunlight from the roof illuminated the bowls and plates. It was a meal I'll never forget. It had never tasted so good. She stewed potatoes and pork trotters, bright red tomatoes, and I think there was even celery. She specially gave me a large, square, thick piece of pork trotters, the size of a teacup. I took a big bite and it went right through my teeth. Oh my! For the first time in my life, I knew something so delicious. I still remember it to this day. The teacher laughed: "Don't worry, I was so worried when I saw you climbing up and kicking the roof down earlier, I thought it would take forever and was going to call for more people. What about the front roof?" "Don't worry, teacher," I said, shoveling down my sixth bowl of rice. The bowl was full; it would be even faster in the afternoon. I carefully secured the roof. The house leaks from the roof, after all. By sunset, it was all good. A warm pot of jasmine tea, costing two hào (Vietnamese currency), was comforting. At this time, the teacher sat and chatted happily:

- You guys are really talented. I don't know how to do anything at all. Growing up, the village sent me to Hue to study, hoping that "one person becoming an official would benefit the whole family." I only knew how to study. I didn't know anything about painting or bamboo. I'll tell you a story from an old Confucian scholar. My teacher and Professor Nguyen Tai Can's teacher were close friends. When they visited, I had to serve them tea. If the roof leaked in one place, they'd move the leak to another. If it leaked in a new place, they'd move it to yet another. It leaked again, and again, running around like crazy. Yeah, it was like that all year round. Why couldn't they just cover one leak or finish it in a day like today? That's how Confucian scholars are, you know. Confucius was teaching around, and he saw a farmer in a field by the roadside skillfully and strongly scooping water with a bucket. His students admired him. Confucius wrote: "Intelligence comes from the mind." It seems Confucianism dislikes practical science. Hahaha…

We left, walking and cycling through the night so we could go to school the next morning.

Associate Professor, Meritorious Teacher Tran Dinh Huouand generations of students

2. Then, at the end of 1975, I received a thesis assignment from Professor Bui Duy Tan on Nguyen Trai. One afternoon, while I was playing table tennis on a stone table under a row of longan trees, Professor Tan poked his head out from the attic on the third floor of the front building and called out, "Hey! Hey! You shorty! Come up here!" I dropped my racket and went upstairs. He scolded me, "Are you going to eat broken table tennis balls? Read a book instead! Tomorrow we're going to the National Library. Here's your letter of introduction. Go to the special archives room and ask to read." He fumbled around and pulled out two dong: "Here's the tram fare! You city dwellers, don't try to sneak in without paying!" I could only tremblingly accept it. At that time, my professor's salary was only 75 dong at most, and he had a difficult family situation. My siblings in Hanoi could barely give him 5 dong a month, and that was already a great effort.

I used to sit in the library, sometimes taking over an hour by tram to get there. On some days, to treat friends to candy, I'd sneak onto the train without paying the fare or walk 10 kilometers in short bursts. Fortunately, in the 1965 mimeographed Philosophy Bulletin, there was an article by Professor Tran Dinh Huou titled "Nguyen Trai." That was a vast opening that helped me realize the path I needed to take. In the introduction, the professor wrote, in essence: What we currently know about Nguyen Trai are only isolated islands, mountain peaks rising after a sea level rise. At the same time, expecting to study his entire geomorphology is truly difficult. This depends heavily on an interdisciplinary, comprehensive, and objective approach.

I am aware that scientific work is very serious and arduous, unlike writing poetry or engaging in casual conversation. The past always comes to us through many changes: war, negation, and especially prejudice. Reading the "TRUE HISTORY" is very difficult. During the lectures and seminars, I tried my best to take notes, record information, and ask questions about anything I didn't understand. The professor's house was still too far away, so I couldn't visit him.

In 1976, I continued my third-year thesis on Nguyen Trai. By then, my professor had moved to Lo Duc, living in a small room of about 12 square meters. I went to consult with him about my future direction. My supervisor was still Professor Bui Duy Tan. By this time, I had become closer to Professor Huou because I knew he was a close friend of my high school teacher, Mr. Dang Luyen, who treated me like his own son. Professor Huou exhaled a puff of smoke from his pipe and suddenly asked, "Vi, let me ask you, do you find philosophy interesting? What do you think of it?" I honestly replied, "I find reading philosophy just like reading a novel; I understand it all!" He burst into laughter. Then, reaching for the bookshelf, he pulled out a thin, handwritten stack of papers and said, "Read this. I'm going to the street to buy a pack of tobacco."

I read quickly. It was a translated chapter of Conrad's "West and East." I finished reading just as the professor arrived. He sat down and asked what I thought. I went on to explain what he had written, his views, and what I had learned from him… The professor seemed pleased and said, "That really shows you understand. To be honest with you, I teach, but I didn't believe students would understand everything I said. Ah, it turns out students do understand! How many people in your class read books?" "The library lends each student 12 books a week. Many students are very enthusiastic." "That's quite a lot! That's great! We didn't get that much during the evacuation; we read very little." The professor picked up the document, lifting it slightly as if checking its weight, then suddenly offered it: "This is for you. I have a typed copy. The department's materials are also available. Take it home and read it carefully."

I've kept that unexpected gift until today, through the post-war famine, through many moves, and through building and renovating houses. My teacher's handwriting is thin and weathered. His sweat still seems salty on those "seven-cent-two-cent" pages from back then. His intellect shines through in every word of his translations.

Throughout 1977, under the guidance of Professor Bui Duy Tan, I continued working on Nguyen Trai to complete my undergraduate thesis. I visited Professor Huou and Professor Phan Dai Doan more often. One was about ideology, the other about history, and both were from "our hometown." I also took every opportunity to go to Thuong Tin, Con Son, Lam Son, Lam Thanh, Vu Quang… sometimes begging for food like a real beggar, trudging along, hungry and suffering.

When the manuscript was finished, besides giving it to Mr. Tran Ngoc Vuong to read and correct the "silly" parts, as he put it, I took the book to my teacher's house. He read it attentively right in front of me and immediately said: "That's strange! To this day, I've never seen anyone call Nguyen Trai a 'Cultural Figure.' How dare you write that? Forget it!" I replied: "Teacher Tan also told me the same thing; people call Mr. Trai by all sorts of 'Stages,' but not 'Cultural Figures.' Look again... but I think..." Because we were now close, I boldly went on and on about my views. Finally, I said: "Nguyen Trai was also a farmer, a very knowledgeable old farmer, teacher." I pulled out a few lines of Nguyen Trai's poetry and commented:One meal, two purposes, many people desire / Two strands, three threads, a curse for the greedy"What is it like to live in the countryside?" ThenThe fields are the masters, the people are the guests."What was that like with agricultural experience? The professor just sat there saying, 'Oh, really! Oh, really! Who told you that?'" (Later, when presenting something to Professor Hoang Ngoc Hien, I noticed that the two of them were very similar in that they kept saying, "Oh, really, really, really"). Fortunately, in 1980, UNESCO recognized Nguyen Trai as a World Cultural Figure.

When it came time to defend my thesis, my professor praised me highly for my willingness to stand up for my opinion.

Students offer congratulations.Associate Professor, Meritorious Teacher Tran Dinh Huou(Fourth from the left)

3. In 1978, I stayed at the university to research and teach, but instead of focusing on medieval literature, I was transferred to folklore. I went to my professor again to ask for his advice. He gave me very clear guidance:

- First, you should work on the Thais. Working on the Chams is complicated, working on the Khmers is too far-fetched, and Mr. Tu Chi has already done a good job on the Muongs; you shouldn't mess around with the chimpanzees. The Thais are very important; the Kinh population is only two-thirds theirs, and their territory is a strategic part of Southeast Asia, having once stretched from Myanmar to Taiwan. They are also a particularly important source of our Kinh heritage. This is no joke; things change drastically, and there are many complexities. I repeat, it's very strategic. I will introduce you to Mr. Dang Nghiem Van; he teaches at the Central Ethnic Minority School, so he has a lot of information.

- Secondly, you shouldn't learn my way of working. I write based on accumulated experience and then refined ideas. I'm not a researcher or an "accountant" like Mr. Hoang Xuan Han taught. If you follow my style, where will you get the experience from, so you'll easily fall into speculation. In our culture, we call it "speaking prematurely." Follow Mr. Can; he's very meticulous, measuring everything specifically and clearly down to the smallest detail. He puts in the effort to research materials, and once he's done, he has an article. Careful research itself is persuasive. That's what you have to teach. Reduce your arguments; immature arguments are a double-edged sword.

I couldn't follow Thai's advice because I couldn't endure the hunger and thirst during several field trips in the mountains. Post-war poverty was a real burden. People didn't even have enough clothes to wear. I did my research. I only understood half of what the teacher said.

In 1980, upon hearing that I intended to return to my hometown to get married, my teacher summoned me. This time, it was the advice of a father: "I've heard the story, and there are two things I'm about to say that are absolutely wrong and unacceptable."

First, you intend to marry her just to take care of your elderly parents, right? That's inhumane. Women aren't slaves for you to use; they're already suffering enough. Marrying someone just to have them "work the fields to support their elderly parents" is selfish and only adds to their suffering. How many times do you get to go home each year? How long will they have to sleep alone? You can't bring her here.

Second, in our generation, husbands and wives are separated due to circumstances. We've learned our lesson, and we can't accomplish anything worthwhile. Don't repeat that. Settling down is the first step to success. You should marry someone from out here, share the good times and the bad, and help each other work. You'll get old before you know it.

I sat quietly and thought, thankfully it was only an intention. He told me this when he was 53 years old. "You'll get old before you know it." This year I'm already 60. Teacher, whatever I've written, I no longer have the opportunity to share it with you. Sometimes I feel like an orphan in this money-driven society. I miss you so much.

Hanoi, January 29, 2015.

(Image collected from the internet)

Author:Nguyen Hung Vi

Newer news

Older news