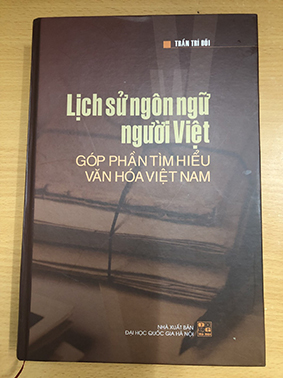

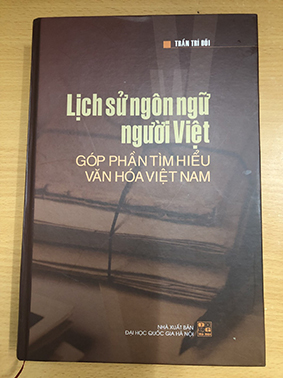

Recently, he published the book "The History of the Vietnamese Language Contributing to Understanding Vietnamese Culture," which has attracted considerable public attention. Previously, some argued that the Vietnamese language, having withstood thousands of years of challenges, has endured and retained its unique characteristics. What is his perspective on this issue, as presented in his book?

| In my opinion, that is a completely accurate observation. In my recently published book, from a linguistic history perspective, I have presented the scientific basis to prove the validity of the above statement. Accordingly, the Vietnamese language is originally an Austroasiatic language. Over thousands of years of development, although the Vietnamese language has borrowed (or rather, borrowed from each other) from the Sino-Sinitic language group, the Taician language group, and even from more recent European languages, etc., there is still a basis to see that the Vietnamese language retains all the characteristics of an Austroasiatic language. This characteristic is manifested not only in grammar but also in the basic vocabulary and, especially, in the changes in phonetic rules within the language. |

|

We can see this most clearly in the fact that, in modern Vietnamese, people still say "nha ngoa" (in "go to kindergarten") using a purely Vietnamese grammatical order; while loanwords from the Sino-Vietnamese language group have retained the Sino-Vietnamese word order, such as "lecture hall" (to go to the lecture hall; giảng: to teach, đường: house; therefore, lecture hall is a place or house for teaching); this order is different from the order in the case of "nha ngoa" mentioned above. That grammatical order is to distinguish what is purely Vietnamese and what is borrowed (from a Sino-Vietnamese language). People who speak Vietnamese daily don't need to pay attention to it because the Vietnamese language has "transformed" the word "lecture hall" (of Chinese origin) into their own language; but researchers still need to know. Or, in Vietnamese, people still use words related to parts of the human body such as "bằng lòng" (agree), "hài lòng" (satisfied), "phải lòng" (fall in love), etc. In the Vietnamese language, what does "lòng" mean? When Vietnamese people say, "Today, the pork offal is very delicious," most people know what "pork offal" includes. No one pays attention to distinguishing between "tràng" (intestines), "gan" (liver), or "dạ" (stomach), etc., which are words or elements of Chinese origin.

The basic vocabulary of the Vietnamese language, dating back to its earliest times (linguistics calls it pre-linguistics), has been preserved. However, what is even more remarkable is that when borrowing, the Vietnamese language requires that those borrowed words respect its own phonetic rules. For example, when Vietnamese people say "I live on the third floor," the word "floor" is of Chinese origin (the Chinese character 閣), influenced by the phonetic changes that occurred in the early Vietnamese language, as briefly discussed in our book. This is why we can say that the Vietnamese language fully retains the characteristics of a language of South Asian origin. Thus, it is precisely through the operation of these phonetic rules that the Vietnamese language has handled borrowings from other languages in its own way, preserving its South Asian identity in language use.

When borrowing words, the Vietnamese language stipulates that those borrowed words must respect its own phonetic rules.

In the book, he wrote, "In the course of Vietnam's historical development, to achieve the rich and distinctive culture we have today, the national language has contributed both as a cultural element and as the most important communication tool for conveying culture." So, how has language developed to contribute to the vibrant vitality of Vietnamese culture throughout history?

|

In the cultural structure of a nation or community, the language or speech of that nation or community has value or a role as a cultural component. On the other hand, language, as the most important communication tool and a product of the nation's or community's thought, is a treasure trove that preserves and transmits the culture of the nation or community that uses the language. As I explained above, during the thousands of years of development of the Vietnamese community or nation, there have been many historical events. However, the Vietnamese language has not lost its characteristics (or its South Asian origins) that the community uses. In interactions (both active and passive, influenced by history), the Vietnamese language has prioritized choosing what it lacks compared to the languages of other communities to enrich its own language while preserving the positive characteristics that its own language already possesses. It is precisely this way of handling language that has contributed to the enduring vitality of Vietnamese culture throughout history. |

Many argue that Vietnamese culture has undergone a process of assimilation and harmonization of diverse elements. So, how does the history of language reveal the diversity of Vietnamese culture?

Throughout the history of human society in general, and of individual nations in particular, no community or country has ever developed while remaining isolated, without interaction or contact with other countries or communities using different languages. Interaction and contact inevitably lead to a process of adaptation and adoption of diverse elements, creating harmony within one's culture or civilization. This is no exception for communities using languages belonging to the Vietic group. For example, the Vietnamese language during the period of domination by the Northern feudal state did not abandon its original South Asian origins; instead, it actively adopted languages it did not previously possess, enriching its language and, along with language, its culture.

Regarding this, you can also consult Professor Mark for further advice. Alves, Editor-in-Chief of JSEALS (Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Association, published in the US), in his newly published 2023 work, "Lexical evidence of the Vietic household before and after language contact with Sinitic," will show how the Vietnamese language has contributed to the diversity of family culture in Vietnam. Similarly, in my book, on pages 261-288, we briefly present that only from the 2nd century onwards did the Vietnamese language "expand" the vocabulary denoting kinship within the family, as well as forms of address. Before that, in the pre-Viet period (i.e., from the 2nd century onwards), the Vietnamese language expressed family relationships in a narrow and direct manner around the parent-child axis; only after contact... Due to Chinese rule, terms like "uncle," "aunt," "cousin," "cousin," etc., only appeared in the Vietnamese language after contact with the Han Chinese. Similarly, before that, forms of address in the Vietnamese language revolved around the "I - you"/"you - "it" (similar to English forms of address), which are still used today but are considered "colloquial." Only after contact with "Chinese culture" did terms of address based on hierarchy, titles, and social relationships become part of Vietnamese culture over thousands of years. Likewise, in the pre-Vietnamese period, the Vietnamese language did not use terms for surnames; but only after contact with "Chinese culture," due to the need for social administration and governance, did terms of address used to identify surnames (such as Hoang, Tran, Truong, etc.) enter the Vietnamese language and society. Even in Vietnam today, the culture of "kinship" is even more extreme than in China. It is thanks to research on... The history of languages that we know shows that this is how the "expansion" or "reception" of cultures among different communities occurs.

This active borrowing or adoption has led some people, based purely on appearances, to mistakenly believe that the languages of Vietnamese-speaking communities no longer retain their South Asian origins and resemble Chinese dialects. Another example is when communities speaking Vietnamese-speaking languages peacefully interacted with communities speaking Thai-speaking languages (as they migrated from the North to the South). The Vietnamese-speaking communities then adopted elements of agricultural culture that they previously lacked, resulting in the diverse and rich Vietnamese agricultural culture we see today.

| For example, on the internet today, we see many "internet scientists" (a term used in an article by Professor L. Kelley, an American currently working at the Royal Institute of Brunei Studies) claiming that there are "tens of thousands of Vietnamese words" similar to Chinese words in Cantonese or Hokkien dialects. However, among these supposedly "similar" words, only what "academic linguistics" calls phonetic correspondences can be established; these "internet scientists" have yet to point out the so-called phonetic law between those words. Isn't it true that in Southern Vietnam, people use the word "tía" to mean "father" or "dad"? Perhaps this is a phonetic variation of the Cantonese or Fujianese word written in Chinese characters 爹 (pinyin: diē; Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation: đa), while in Vietnamese culture it's called "cha" (in the novel "Water Margin," the Chinese character 阿爹 with the Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation "á đa" is translated as "Oh father"). Here, the word "cha" (of Chinese origin) and "bố" (of South Asian origin) are still used simultaneously in the Vietnamese language; South Asian culture hasn't been abandoned. |

|

Furthermore, the Vietnamese and Thai people, having lived together peacefully in Southeast Asia for thousands of years, borrowed words related to agriculture from each other. Thanks to this, the Vietnamese language has added words like "canal," "ditch," "flood," etc. These words are not the entirety of the Vietnamese vocabulary related to agriculture. They are only a small part, merely borrowed words that enrich the Vietnamese language.

How does studying the history of the Vietnamese language help us understand the origins of Vietnamese culture?As we all know, when studying the history of the "origins of Vietnamese culture," the principle of historical science dictates that these cultural phenomena must have been recorded by "contemporaries." However, when we talk about the "origins of Vietnamese culture," we mostly rely on folk legends and historical records from Chinese texts from the 10th-11th centuries and earlier. For us, "folk legends" have a historical core; however, they are not entirely identical to history. As for the recorded events concerning the Vietnamese community in the South in Chinese historical texts from the 10th-11th centuries and earlier, they are both scarce and unsystematic. But more importantly, these records are often not from direct witnesses but are based on hearsay, compiled by scholars who generally lived in the capitals of the Northern dynasties. Therefore, what belongs to the culture of the Vietnamese community from about the 3rd century onwards often depends on the ways or attitudes of "recording" or "annotating" those records by Chinese scholars from about the 3rd to the 10th centuries.

To supplement or overcome that shortcoming, in an interdisciplinary approach, alongside archaeological data, prehistory scholars consider linguistic data used by historical linguistics to be one of the most important sources. When studying "The Origins of Agricultural Societies," Professor Peter Bellwood observed, "In fact, the history of language reveals many important things that most scholars outside of linguistics seem completely unaware of. I am beginning to realize that some aspects of human history must be entirely different from the approximate reconstructions of archaeologists based on comparative cultural records preserved in ethnographic documents." He argued that, “To understand the processes of cultural and anthropological diffusion throughout history, we need to consider the materials of many different research disciplines. First, we have archaeology, the study of ancient societies from the material traces they left on or below ground…But archaeology also has clear limitations because the evidence is often fragmented and sometimes very vague…Second, we have comparative linguistics…Comparative linguistics has an advantage over archaeology, which is that the linguistic database, in the case of a living language, is usually complete.” Here, I will only cite the case of Professor Peter Bellwood as an example to illustrate my point. This is a reality in current prehistoric research.

Therefore, studying the history of the Vietnamese language allows us to reconstruct the linguistic picture of the community at each specific historical period; then, cultural researchers will be able to "read" or "recognize" the characteristics of the cultural origins of the Vietnamese people. This is how historical linguistics, specifically the history of the Vietnamese language, contributes to the study of the cultural origins of the Vietnamese people in particular and the study of the cultural origins of a community in general.

In my personal observation, for in-depth scientific content, state management agencies often "ask" or "ask" people with official positions in scientific institutions rather than delegating the task to actual scientists. Professor Tran Tri Doi commented.

How can we summarize the process of formation and development of the Vietnamese language through different historical periods?As presented in our published book, the formation and development of the Vietnamese language can be summarized through the following historical stages. Accordingly, the Vietnamese language has developed into the following stages: the Proto-Vietic stage, corresponding to the "Dong Son culture" period, meaning that the people using the Vietnamese language were indigenous inhabitants (homeland) in Southeast Asia; the Archaic Vietmuong stage, corresponding to the period of Chinese rule in Vietnamese history; the Vietmuong common stage, belonging to the early period when the Dai Viet state was independent from the North; and the Old Vietnamese stage (13th-15th centuries) when Vietnamese and Muong developed into independent language entities. Then, it developed into the Middle Vietnamese stage and gradually expanded southward, reaching the Modern Vietnamese stage in Vietnam by the mid-19th century. Each of these historical stages of development has contained a wealth of information about Vietnamese culture. With this historical development, the Vietnamese language acquired the Nôm script (13th century), the first writing system in history, and in the 17th century, the Latin alphabet was added. The emergence of the Nôm script significantly contributed to the qualitative development of the Vietnamese language, transforming it into a literary language in Vietnamese life. Simultaneously, based on an analysis of historical linguistic changes, this book demonstrates that the name Lạc Việt is an autotonym of the community of Mon-Khmer speakers residing in mainland Southeast Asia, including those speaking languages belonging to the Vietnamese language family.

During our discussion, we realized that historical research is complex, persistent, and requires long-term investment. So, has the relationship between the history of language and the history of Vietnamese culture received adequate attention and research investment today, and why?From our perspective, the relationship between the history of Vietnamese language and cultural history has only recently begun to receive some public attention. The following objective reasons have contributed to this delay. Firstly, it stems from the field of linguistics itself. Although a subfield of linguistics, it lies at the intersection of many other social sciences and humanities, making it extremely complex and, in both literal and figurative senses, "dry." In our country, where something is so "complex and dry," few people are willing to venture into it. For example, in the late 20th century, to obtain materials for a few articles in this area, we had to travel extensively throughout the western regions of Quang Binh, Ha Tinh, Nghe An, etc., regardless of the rainy season or the scorching summer, even risking our lives. With few specialists, how can other scientific disciplines utilize our work? Furthermore, in Vietnam, the scientific community, especially those in charge of managing scientific research related to cultural origins, often believe that the results of historical research alone are sufficient to form a final opinion. Only recently, when externally demonstrated a new interdisciplinary approach that overcomes the shortcomings of research, has people begun to acknowledge the contributions of comparative-historical linguistics to the study of cultural history. But acknowledging contributions is one thing, and promoting them is another. Thirdly, it lies with those responsible for managing scientific research in this field.

Vietnamese language lesson for students at Pom Han Primary School, Lao Cai City.

Therefore, when you ask, "Has the research been adequately invested in?", the short answer is "no." And when you ask further, "Why?", in my personal opinion, the three reasons I offer for arguing that the relationship between Vietnamese linguistic history and cultural history has received very little attention already show why, in our country, when presenting Vietnamese cultural history, people are "comfortable" with the methods used so far and the existing knowledge we have. To elaborate on this, we would like to cite a case study regarding the handling of public opinion related to the name Lac Viet (雒 越) as an example. This truly illustrates the difficulties in promoting research on the relationship between Vietnamese linguistic history and cultural history in our country today.

Faced with numerous difficulties regarding source materials, research time, and limited investment, how did he and other linguists organize the study of the history of the Vietnamese language?

It can be said that the study of the relationship between the history of Vietnamese language and the history of Vietnamese culture faces many difficulties in terms of documentation, research time, and investment in assembling a team. How to do it? Almost impossible! There are many reasons, but one of the most obvious is that, broadly speaking, the comparative-historical linguistics subfield requires too much effort, yet its research results are not immediately applicable (because it is a fundamental science) but only serve as a basis for various other social sciences and humanities subfields. In other words, it seems that for us, research in this field is acceptable, but the lack of research doesn't harm anyone. This approach, as we have analyzed above, is essentially due to our current complacency with existing scientific conclusions regarding the origins of Vietnamese culture. Meanwhile, in neighboring countries or countries with developed social sciences and humanities, people think differently and are not entirely convinced that the existing explanations on this topic are scientific truths. It is very possible that content related to the history and culture of Vietnam from a linguistic history perspective will be developed by the international scientific community based on their research results. In that case, those interested in the issue will immediately understand what our approach should be. Our dream (previously shared by Professor Nguyen Tai Can, Professor Phan Ngoc, researcher Ho Hai Thuy, etc., and myself) is for the comparative-historical linguistics subfield to build a true "Etymological Dictionary of the Vietnamese Language" to contribute to the study of Vietnamese history and culture, but it seems (or rather, not just seems) difficult to achieve.

Perhaps one hope lies in collaborating with historical language research centers interested in the issues of Vietnam and Southeast Asia. However, in today's era, collaborative research must be based on equality, especially equality of resources, to achieve equal results. Meanwhile, in Vietnam, based on my personal observation, for specialized scientific work, state management agencies often "ask" or "ask" those in positions of authority within scientific institutions rather than delegating tasks to actual scientists. Furthermore, not all those in positions of authority within scientific institutions genuinely care about science and are true scientists. Selecting the right experts in a particular scientific field to assign tasks is more effective. To achieve this, not only linguists but also research managers must work together in organizing research on the history of the Vietnamese language.